Every morning, exactly at nine o’clock, a short, slender man with a hat on his head and stiff shoulders would slowly open the door and head toward the right corner of the store, where the take-out coffee was served. Into the steaming liquid, he’d first pour a little milk, then sugar, snap on the lid, grab a sandwich from the fridge, and join the line. The young man working the register immediately noticed the regular customer but didn’t greet him right away—mornings were always busy.

“Good morning, Igor!” the frail man called out when his turn came. “How are you managing in our desert heat?”

“Much respect, Mister Tony. I’m surviving. Honestly, it’s a lot easier to endure the sun and heat than bombs and shrapnel!” replied the young man, speaking English with a heavy accent.

That Friday, like every Friday, Tony picked up his breakfast and played the lottery. Over time, Igor had memorized his numbers—9, 19, 29, 39, 49…

“Hopefully, the madness in your country will end someday!” added the man with the cap. “All the best, Igor. See you tomorrow!”

As soon as he stepped outside, Tony approached a homeless man and handed him the sandwich and coffee. The scruffy young man slowly pulled his hands from the pockets of his filthy pants, accepted the food and drink, nodded, and went behind the store to share breakfast with his girlfriend. The man with the hat pulled a bunch of keys from his pocket, spun them around his finger, then got into his pickup truck and left the parking lot.

“He does that every morning,” thought the cashier, scanning a pack of cigarettes for two young men in work uniforms.

“What the hell do they put in these things to make them so expensive? Weed and cigarettes will cost the same soon!” grumbled the uniformed plumber as he paid the bill.

Igor let his coworker take over the register so he could make a fresh pot of coffee. It had been a year since he started working at this gas station, and it felt like he’d been a clerk his entire life. Just two summers ago in Kyiv, he was teaching math. His students loved him, his colleagues respected him… He had fled to America to escape senseless war and ended up in the heart of Arizona working as a cashier. He cleaned the parking lot, scrubbed floors, and most of all, enjoyed stocking the cooler—his only chance to cool down a bit during the unbearable desert summers. In rare moments of solitude, he’d quickly organize the shelves, stack beer, juice, and frozen food, then sit on a crate and check updates from the Ukrainian front on his phone. He had escaped that hell, but his parents and younger sister hadn’t. “Severe Russian retaliation after Ukrainian drone strikes. According to health organizations, more than a million have been killed or injured since the conflict began.”

For most foreigners starting their immigrant journey, every day looks like the one before—work, overtime, home, food, sleep. Yet in the monotony of his routine, Igor noticed that Tony had stopped coming by since that Friday.

A month later, it was Wednesday, early morning—Igor’s day off. He wasn’t lucky enough to enjoy weekends like regular folks; according to the schedule, he rested on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. He set his alarm for six to go get a chest X-ray. During his visa medical screening, he tested positive for TB. Immigrants from Eastern Europe (including the former Yugoslavia) often struggle with the tuberculosis test, having been vaccinated at birth—resulting in lifelong false positives in Western countries screenings. Some twenty years ago, a Russian man spent two months in quarantine for the same reason. After various medical boards reviewed the issue, it was explained that in many countries, babies are still vaccinated against this eradicated disease. Since then, U.S. officials no longer panic, but an X-ray is still mandatory.

Igor quickly drank his tea, threw on a pair of shorts, the thinnest T-shirt he owned, and set out—because in Arizona, going anywhere without a car becomes an adventure. The immigration office was about thirty kilometers away, requiring three different bus transfers. A taxi was too expensive, and he didn’t have a credit card for Uber. He needed to get that screening done quickly, as the deadline was looming. “If I don’t finish today,” he thought, “next Tuesday will be too late… and knowing them, they might just deport me!” He walked to 7th Street, took a bus to Thomas, then another to Central Avenue. At the bus stop, an old woman gave him advice:

“You must be new in Arizona. In summer, we don’t walk around without long sleeves and pants… Shorts are for people with cars!”

At the immigration office, he waited for two hours, worrying whether he’d finish before closing time. “At least no one cuts the line like they do back in Ukraine,” he thought, breathing in the stale, chilled air. When his turn came, he picked up the forms and headed straight to the hospital. He prepaid for the exams and received two referrals—one for imaging, the other for a pulmonologist. While trying to locate radiology on the hospital map, he felt someone grab his arm.

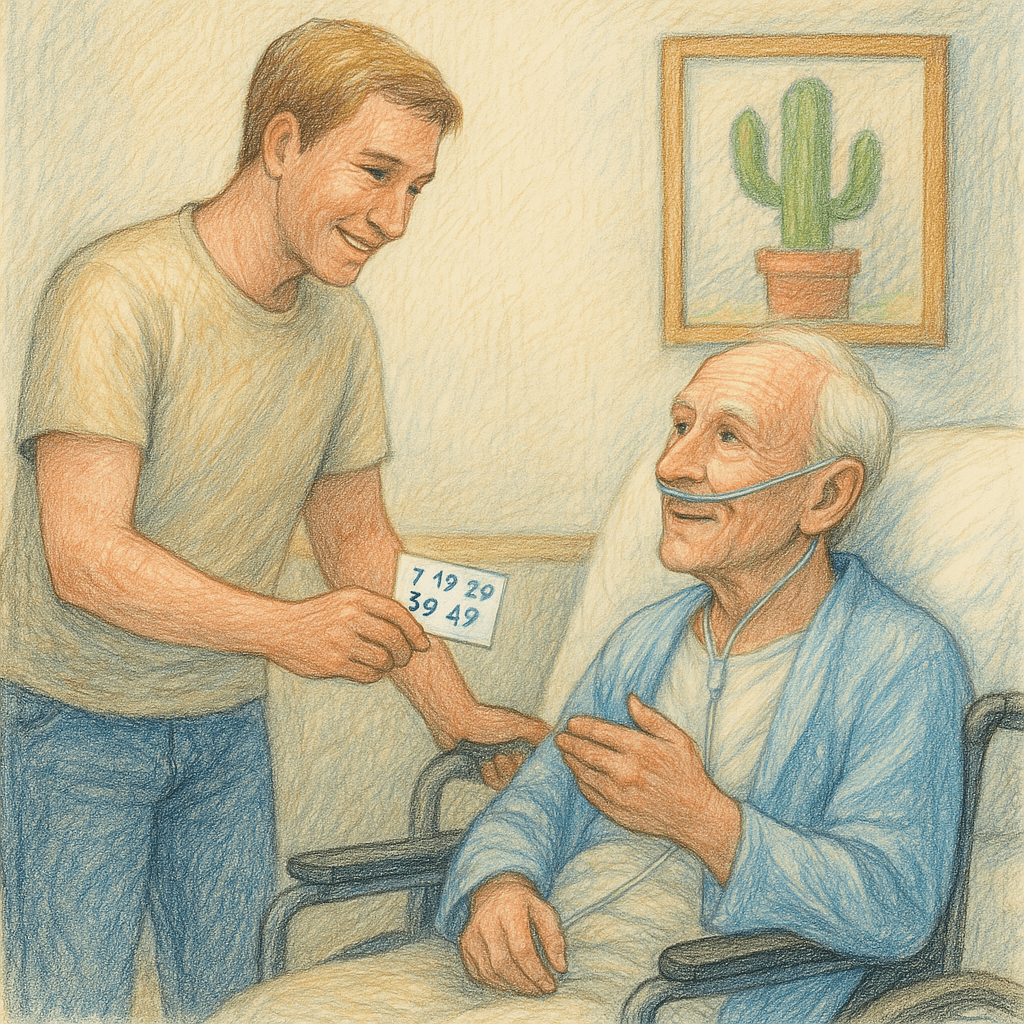

“Mister Igor, greetings!” said Tony, sitting in a wheelchair. He wore a hospital gown, a thin tube delivering oxygen into his nose.

“What happened, dear Tony?” asked the younger man, startled.

They moved away from the reception and headed to a nearby cafeteria. The nurse caring for Tony wheeled him to a table, promising to return in half an hour. Igor brought two coffees and a sandwich for his friend.

“I didn’t get you a lottery ticket—drawing’s on Saturday,” he said, placing the referrals aside.

“Saturday’s far away, my young friend. I might not make it. But don’t worry about the lottery—I won’t be needing money anymore,” Tony replied with a bitter tone.

Igor watched people pass by. Some were rushing, eyes glued to papers, searching for the right floor, department, or office… Doctors, nurses, and hospital workers in colorful uniforms moved with purpose. The support staff—those noble souls enduring the hardest moments of their patients’ lives for pitiful wages… The young man could no longer avoid Tony’s gaze, which hinted at an impending truth. He took a sip of coffee, looked the man in the eyes, and quietly said:

“I’m listening, my friend.”

Tony spun his keys around his index finger, adjusting the oxygen tube with his other hand. In a halting, distant voice, he began:

“Well, Igor Borisovich, my young friend, my story starts on September 9, 2019, at nine in the morning, on the ninth floor of this hospital—and you won’t believe it—in office number 919. That day, they diagnosed me with that disease people often live with but rarely survive. In this ‘lottery,’ all my organs participated, but the lucky winner was the nastiest one! What I, as a former car salesman, would call—human exhaust pipe! They found it too late, and I didn’t want them cutting and patching me up. That very day, I quit my job and started spending my savings. I’ve long been divorced, we had no children, so there’s no one to mourn me. It’s been nine months since then, and I’m now happier than I ever was when I was healthy!”

A ten-year-old boy with a bandaged head was wheeled past them, explaining to his parents that the helmet wasn’t strapped on right, but swearing he was riding the electric bike slowly. At the next table, an elderly man gently fed the love of his life a chocolate muffin. Tony asked a passing nurse for a glass of water, then continued.

“That’s when I started coming to your store regularly. It’s close by, and I noticed the homeless gather there. I began doing small good deeds and always bought a lottery ticket…”

There’s something in human nature that bends even the most tragic tales back toward ourselves. “So here’s America—huge, rich, and people are still sad, sick, dying…” Or as his grandfather used to say, “There’s no death without Judgment Day!” Igor mused inwardly. Then, almost unconsciously, he stood up and touched the shoulder of the only friend he’d made in America. His eyes welled up as he tried and failed to suppress a sob. That kind old man had always been dear to him, but now he wept for everything he’d endured in recent years. It had all piled up and had to come out.

“Come on now, don’t go all gloomy on me—you haven’t even heard the best part yet! I sold cars for decades. People say we’re all crooks and liars… maybe they’re right, I don’t know. My whole life I played those sweepstakes, bought lottery tickets and those scratch-off scams. Never won a damn thing, believe me! But after I got the diagnosis, I decided to play just one ticket—a single one—with all nines. And twelve Saturdays later, I hit the jackpot…”

Igor flinched. “If there had been a nine instead of those twelve weeks, that would’ve been too much!” thought the young man, suddenly reminded of a joke about an old man who, after winning the lottery late in life, built a public restroom so people could “piss on his luck.”

But Tony wasn’t joking. His brow was furrowed, wrinkles deeper, eyes red and dry—there were no tears left.

“Yesterday, my lawyer called—he said it’s all settled. I’ve donated most of the money to various foundations that fund treatments for children—those outrageously expensive surgeries without which they wouldn’t survive. I also gave to some artists and poor students who want to study… Here’s my lawyer’s number—he’ll help you get your family out of Ukraine.”

All the pain Igor had managed to bury deep in the depths of his Slavic soul surged to the surface. Tears streamed down his face as he struggled in vain to stifle his sobs. That kind old man had always been dear to him, but now he wept for everything he had endured over the past few years. It had all built up—and finally had to explode. Just then the nurse returned, and they all accompanied Igor to the radiology wing.

“Stop by when you can. I’m on the third floor, room 351. As you can see—no more nines in my life!” Tony smiled.

“Unless you add up the digits in your room number!” replied the Ukrainian mathematician.

Leave a comment