In the lovely town of Tombstone, where the Santa Cruz River no longer flows due to drought, only one memory remains — a daily show in the center of town, nearly every evening. In the theatrical reenactment of the historic gunfight at the OK Corral, for two decades the role of Wyatt Earp was played by James Russell. But then age caught up with him — his voice and strength began to fail, and younger actors took over the show. It was five or six years ago when the director asked him for a drink after the “shootout.” James knew something was up. The tattooed brat of a director “carried a snake in his pocket” and had never bought a round in a saloon. That night, he told James that from now on, he’d be playing the villain — the outlaw Clanton.

From that day on, James was no longer the same man… Once a charmer and joker, beloved by both locals and tourists, now he sat silently in the corner of the dressing room — hollow-faced, eyes lost in thought.

In Tombstone, the sun scorches from early morning, and by midday, the asphalt begins to melt. Wooden houses crackle in the heat, and shadows retreat under porches. The town looks like a film set. The main street, with its saloons and faded Colt revolver ads, becomes a stage every day. At the far end, near the mock sheriff’s office and replica jail, stands an improvised set. Every day at high noon, the shootout at the OK Corral is reenacted. Visitors sit on wooden bleachers, waiting for gunfire and the triumph of good over evil.

Before stepping on stage, James would always twist a silver ring on the pinky of his left hand — an old habit, a charm against bad luck. The ring had been a gift from Mary, the woman he once loved madly but lost to his own stubborn pride. They had acted together across Arizona, performing side by side. Mary was fiery, witty, clever. Her hopeful, electric gaze always nudged him to wake from provincial slumber and leap toward adventure and uncertainty. She begged him to leave with her, but the “head sheriff” stayed put.

She left Tombstone and, after years of wandering, reached Hollywood. She never became a star, but made a modest career — appearing in background roles remembered only by those who paid close attention. They never saw each other again.

After one show, James sat outside the saloon, staring into the dry riverbed of the Santa Cruz. Just a trace remained where water once flowed — a few puddles, some greenish silt in the desert sand.

“This river is like my life,” he muttered. “The bed’s still here, but the water’s long gone.”

Suddenly, a man in a loud shirt approached. He looked like a tourist, but walked with the confidence of someone who knew exactly where he was headed.

“You played that fall and slow dying better than most professionals I’ve hired!” the stranger said.

James looked up.

“So, you’re a movie guy? If you buy me a whiskey, maybe I’ll fall over again.”

The man introduced himself: Roger, a producer of low-budget westerns. He was looking for someone to play an aging outlaw — a man of few words, whose eyes told the whole story. After three drinks, James began to open up. He spoke of acting, of love, and the chances he let slip. People told him he should go to Phoenix, maybe Los Angeles… But he stayed. Alcohol. This town. One makeshift stage — that was his life.

“How did you find me?” he asked, not really expecting an answer.

Roger took a sip of coffee and studied him.

“My mother recommended you. Mary Bush,” he said with a soft smile.

Silence. James coughed and looked carefully at the young man. The familiar lines of his face, the fire, the passion for art… He saw everything he had once loved in the woman he never forgot. He said nothing — just gripped his ring and twisted it slowly. He didn’t want words to ruin the moment.

He ordered another drink and asked Roger to leave the script and his number.

“Just so you know — shooting starts in a month,” Roger said as he toasted the local cowboy, packed his things, and drove off in a Tesla.

James called the Tombstone director that night to ask for some time off. The pretentious kid responded,

“Big deal, I can get any drunk to fall during the shootout.”

James swallowed hard, hung up, and muttered,

“You’ll see, you arrogant little mule, who you’re calling a drunk.”

He walked to the dry river, stared at the dusty bed, and thought about his wasted life.

“That role, no matter how small, is better than this wordless tumble in the dirt.”

He smoked a few cigarettes, went home, and found a package sticking out of the broken mailbox. He ripped open the envelope and recognized the handwriting.

My dearest Sheriff,

My sweet Wyatt,

You’ve met Roger. I’m sure you saw how much you have in common. I told him all about you — what a good actor and man you are. Take the role and come soon!

Yours, M.

He opened the large yellow envelope containing the script for Dust and Silence. The room was stuffy, despite open windows. No breeze. Just dust — and silence.

He brewed coffee, lit a cigarette, and read the script in one sitting. Then read it again. He texted Roger his acceptance. The reply came swiftly — with the address of a motel in Yuma where he’d be staying during filming.

A week later, he pulled out an old suitcase, the same one he once took on tour across Arizona. Mary had traveled with him back then. It still smelled faintly like her. He twisted the ring again and packed only the essentials.

Before leaving, he glanced once more at the Santa Cruz. The river no longer flowed — but it was still a river.

Maybe he too was still that actor, as they once called him?

At the bus station, he avoided familiar eyes. He wasn’t just leaving Tombstone. He was heading for something bigger: maybe… a new beginning?

That same evening, at the motel, he met the film’s director — a young man who clearly distrusted the amateur actor from a cowboy town. But then Roger, the lead producer, arrived. He ordered dinner, and the conversation lasted late into the night.

First day of shooting.

James put on the costume and waited for his scene. He didn’t have many lines. He played a man who had already said everything there was to say.

“Camera?” — “Rolling!”

“Sound?” — “Rolling!”

“Action!”

They filmed the scene where his character sits silently as the son he never met dismounts and walks toward the stranger. They stared at each other. James let a single tear fall, then embraced the young man tightly.

“Cut! Sold! Perfect!” the director shouted.

That evening, they sat outside the motel. The cowboy from Tombstone drank bourbon. The producer, beer.

“I hoped you’d come, but I was afraid you’d turn down the part,” said Roger.

“I hesitated… but I couldn’t say no to you,” James replied.

Silence.

“When I was little,” Roger began, “my mom used to tell me about you. Always with a certain caution. She loved you more than she cared to admit. I could only imagine you back then. Now I don’t have to.”

James raised his glass.

“To the roles we never played.”

“To a new beginning. Cheers!”

At that moment, the director appeared. He stood before the veteran actor, bowed slightly, and offered his hand.

“Mr. Russell, what you did today… I didn’t think silence could be louder than a monologue.”

James looked up.

“Neither did I. Not until today.”

They were alone again. Roger brought out a bottle of whiskey from the motel room.

“I’m still not sure if you’re my father.”

“I’m not either, son… but maybe that doesn’t even matter anymore.”

“How can it not?”

James looked up at the cloudless night sky and said softly:

“What matters is that now… we’re in the same frame.”

Filming wrapped.

Cameras packed, costumes sent to dry cleaning. Most of the crew had left. Only a few techs remained, plus the producer, a supporting actor, and one unfinished film — waiting for editing and an audience.

James sat under the motel awning, waiting for the cameraman to drive him back to Tombstone. Now, as a “star,” he had a ride arranged.

Then, a dark blue car pulled into the parking lot. A woman stepped out — wearing a cowboy hat and sunglasses. She walked slowly, but tall and steady. She stopped in front of James, removed her glasses, and looked at him for a long time.

“So you really came,” she said.

“When you called, I realized I didn’t want to die a bitter old man.”

They sat beside each other, quietly, for a while.

“I saw the way he looks at you,” she said. “The same way you once looked at me — that night after our last performance together. But Roger’s not yours.”

James said nothing. He stared into her eyes — still green, fiery, restless… just like before.

“His father was a producer from Chicago. Never acknowledged him. Never even saw him. So I invented a father. I told Roger his dad was just, a little stubborn, but always true to himself.

I taught him to walk like you. To keep quiet like you.”

James nodded.

“So… he grew up believing in a legend?”

“No,” she corrected. “He believed in the truth.”

James looked off into the distance — at the sky, the shadow of a tree.

“Thank you,” he whispered.

“For what?”

“For making me a father — without me knowing. And for letting me feel it before I go.”

Mary placed a hand on his shoulder.

“You’re not going anywhere soon. You’re too stubborn to die quietly!

You’re not Clanton or Wyatt Earp anymore. You were and always will be — my James Russell.”

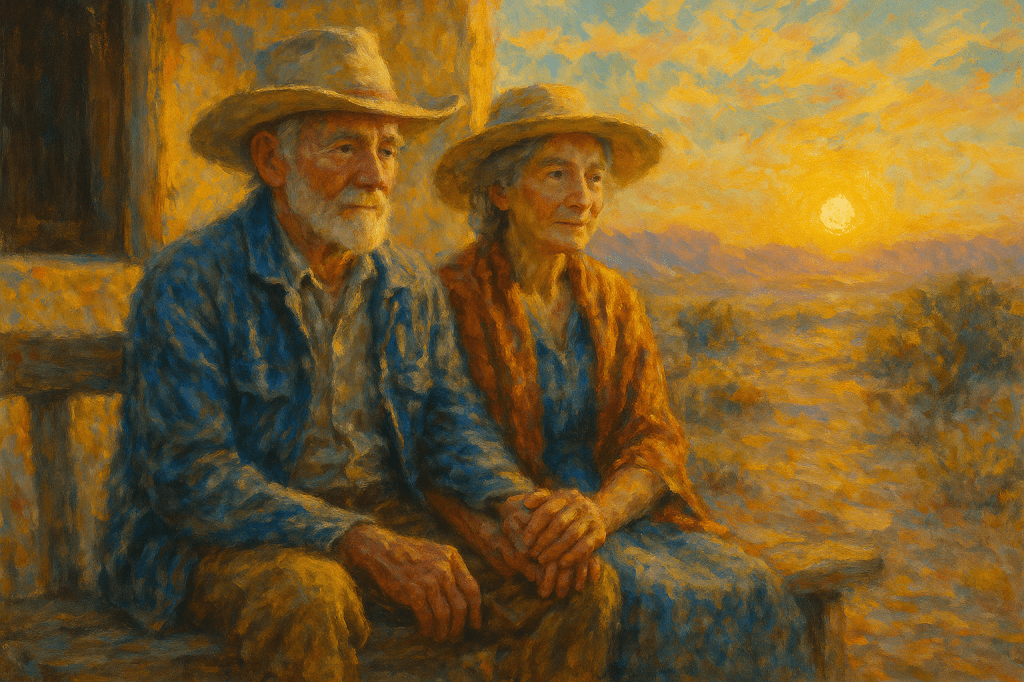

The sky changed color. From gray to orange, then gold.

The breeze was faint, still shy to disturb the day.

James and Mary sat on a wooden bench in front of the motel.

Before them — an empty bottle and ash from too many cigarettes.

The sky lightened slowly. As the sun rose over the desert, their hands met at the middle of the bench — fingers intertwining like two shadows recognizing each other after years of wandering.

And there they stayed.

Leave a comment