There comes a moment in life when a person realizes they no longer wish to change their habits, because those habits long ago ceased to be small rituals and have turned into the structure of their everyday life. After sixty, it’s no longer the adrenaline of new beginnings that moves us, but the serenity of a familiar rhythm. What we once did on a whim, by chance or out of impulse, now becomes an essential part of the day. Habits are like architecture: they build walls that make us feel safe and open windows through which we already know what we will see. With age, rituals stop being charming little quirks and become our mental compass—or, as the younger would say, our GPS. It’s the best way to cope with a world growing more chaotic by the day.

And so, every time I land in Serbia, everything unfolds in the same order. I unpack my suitcase and push it under the bed in a room that hasn’t been mine for years but still smells like childhood. No matter how often I promise myself to “improvise a little this time,” I end up doing exactly the same.

Bakery, tavern, bookstore…

First—the bakery. Not just any, but the one where pastries are still measured by sight, not by scale, and where the rolls are so good that only the French ones come close. That’s where the first conversations with strangers begin—about the weather, politics, rising prices. In that brief ritual, while waiting in line, every year of distance between me and the city disappears as if it never existed.

Next comes Stara Srbija, the tavern that looks exactly as it did twenty years ago: the same stain on the wall, the same smell of cooked meals, smoke, and alcohol. There I meet old colleagues I haven’t seen since my last visit. The conversations are the same but no less dear—grandchildren, sports, nostalgia, who won the NIN Award this year. After two hours, I haven’t learned anything new, but I’ve recharged with familiar warmth.

The next stop is the Laguna bookstore. I browse the shelves, leaf through the books, and buy a few titles I’ll, as always, not read until I’m back in Arizona. I don’t know why, but in American silence, it feels best to read what I brought from Serbia.

And then, when the city quiets down and retreats into its evening routine, when the lights go out and I return home, begins that time of day reserved for old books. On the shelf in the living room, about fifty titles await me—survivors of all the moves, renovations, and “rational decluttering.” I always pick one at random, and it becomes my companion throughout my brief stay in my hometown. This time I “grabbed” Tolstoy’s Notes of a Madman. I read it slowly, a few pages each night, the way one drinks Turkish coffee—with relish, unhurried, savoring every sense. While the TV hums in the background about “historic speeches” and “decisive negotiations,” I stumble upon lines like this:

“Today they took me to the provincial office for observation, and opinions were divided. They decided I was not insane, only because I tried my best not to give myself away. I didn’t, because I fear the asylum; I fear they’ll prevent me there from pursuing my mad work. They concluded I’m prone to emotions and something of the sort, but otherwise of sound mind.”

The next day—my walk. First through the park, the same one where more than half a century ago I chased a ball. Now I walk slowly, stopping by the same benches and trees. I always meet someone there: a schoolmate, a former colleague, a cousin who’s aged faster than I have. The conversations are short and always alike—health, children, America.

My path almost always leads me farther, to Šumarice, where history and silence touch. As I walk through the woods, time itself seems to move slower. In the evening, I wander aimlessly through the city center, recognizing faces in my imagination as if we had grown up together. Taxi drivers argue about politics, a chestnut vendor and a pensioner debate world affairs as if they were headed to a UN Security Council meeting the next morning. I shrug, return home, pick up the book, and turn the page:

“Until I was thirty-five, I lived like everyone else, and nothing peculiar could be noticed about me. Such things happened to me only in early childhood, up to the age of ten, and even then only in fits, not constantly as now.”

Meetings with friends are usually short and on weekdays. Everyone has their own life, family, and weekend plans. Our encounters are brief, spontaneous, and sincere. We meet, talk about everything and nothing. No one tries to sound profound—we leave that to those sitting in TV studios explaining the world. And Tolstoy, after all, still has the final word:

“I remember, once I was getting ready for bed, I was five or six. My nurse, Yevpraksia—a tall, thin woman in a brown dress, with a cap on her head and loose skin under her chin—undressed me and put me in bed. ‘I’ll do it myself,’ I said, climbing over the railing. ‘Come now, Feodyenka, see how good Mitya is—he’s already asleep,’ she said, nodding toward my brother. I jumped into bed, still holding her hand. Then I let go, kicked my legs under the blanket, and tucked myself in. It felt so wonderful.”

Photographs, drums, optimism…

One afternoon, instead of following my usual route, I stopped by the city gallery for an exhibition dedicated to student protests. The place was packed: high-schoolers with backpacks, professors with serious faces, parents of the “children” in the photos. I watched a couple, holding hands, moving from photo to photo, searching for their son’s face. “He’s here somewhere, I’m sure he is,” the woman kept saying, pausing before every frame. They didn’t find him in the pictures, but they did in a student message pinned to the wall:

“For those who can’t be with us—thank you for teaching us to believe that we can.”

The rhythm of drums coming from the corner filled the room, along with a quiet sense of optimism. At home, on the nightstand, my book awaited:

“Like all mentally sound boys of my time, I went to grammar school, then to university, where I graduated from law.”

One morning, while I sat on a park bench, an old schoolmate approached. We hadn’t seen each other in years. “You know I lost my house?” he said immediately. “A fast-track bailiff decision. Sold it over an unpaid electricity bill—seventy-four thousand dinars.”

He paused, then added, “You know, Serbia must be the only country in the world where you can’t be sure you’ll live if you fall ill, work if you’re honest, or reach retirement if you’re diligent. But one thing is certain—you will pay your bill!”

When I got home, I opened my book where I had stopped the night before. I read aloud, as if trying to understand a world where someone loses a home over a bill, while others still strive to ‘wisely increase their wealth’:

“My wife and I had saved money from her inheritance and my convictions about redemption and decided to buy an estate. I was unusually interested in increasing our property—as one should be—and particularly in doing so wisely, better than others…”

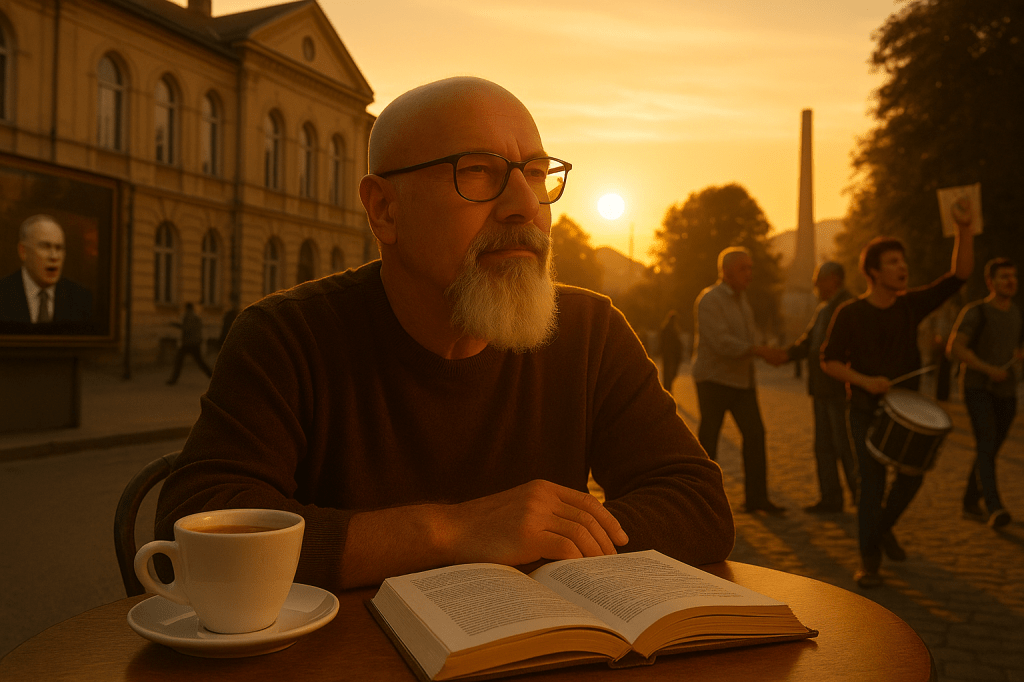

Days passed. Instead of walking the same paths, I spent most afternoons at a café in front of my old high school. That’s where I meet friends from youth. Someone always drops by—a history teacher counting days to retirement, a classmate who says nothing has changed except that we now wear glasses and talk softer. In that mix of planned meetings and accidental encounters, there’s a kind of comfort. In a world teetering on the edge of a nervous breakdown, my little routines still feel like proof that sanity hasn’t completely vanished.

And then inevitably, it’s time to return to America. I pack my habits and rituals along with my belongings, carefully placing them between souvenirs and the books from Laguna that, as always, wait their turn to be opened on the other side of the ocean.

On the plane—an unexpected scene. A few rows ahead sits a group of Belgrade high-school seniors. Twenty or so boys and girls, bright-faced, polite, well-mannered. At first, I thought they were athletes—but no, they were invited to visit the United Nations. Some are flying for the first time, some leaving Serbia for the first time, but all speak of the trip with a seriousness and respect rarely seen today. One girl said she wanted to become a diplomat “to represent Serbia the right way.”

Watching them, I realized that this generation carries within it something we older ones may have long lost: the belief that the world is not only a place to survive, but a place to improve. And right there, between clouds and the ocean, I asked myself: does Serbia deserve such a generation—decent, curious, ready to listen and understand even those they disagree with? And, perhaps even more—do the United Nations deserve such visitors, young people who still believe that once-prestigious institution can be something more than a stage for endless speeches and diplomatic clichés?

I arrive home, where the woman of my life awaits—with a new layout. She’s moved the plates in the kitchen, rearranged the wardrobes in the bedroom, and the shelves in the bathroom. It will take me at least a week to find my way again—maybe a month. Because old habits, after all, are not easily abandoned.

Leave a comment