The year 2026 may not bring a major, symbolic rupture, but it will confirm what has already become obvious: processes set in motion ten or more years ago have entered a phase in which they can no longer be stopped, only managed through their consequences. The world is not entering a new crisis, but a state of prolonged instability. Politics in the United States, Europe, and the Balkans enters 2026 without clear answers, yet with increasingly rigid positions. It is a combination that produces no solutions, but prolongs conflict under the illusion of control.

TO THE RIGHT, MORE CONSERVATIVE, MORE RADICAL…

In the United States, 2026 is an election year for the Senate and the House of Representatives. Regardless of the outcome, the political system remains deeply divided. Elections no longer function as a mechanism for resolving conflict, but as confirmation of two social worlds that refuse to recognize one another. Compromise is perceived as weakness, and institutions as obstacles to “real” politics. In this environment, immigration remains a central issue because, within the existing political framework, it is structurally insoluble. The paradox of American politics is becoming ever more evident: the economy depends on immigrant labor, while the political narrative survives on the promise of stopping immigration and deporting those already present. Tighter border controls and restrictive laws do not reduce migration flows, but instead create more people without status, rights, or political influence. Thus emerges a layer of the population that is economically indispensable and politically undesirable. In the long run, this is a more unstable and dangerous model than the open system that existed for decades.

The European Union enters 2026 weary and disoriented. Enlargement is effectively frozen, a common security policy exists mostly on paper, and the gap between the center and the periphery continues to widen. The right is gaining strength almost everywhere, even where it is not formally in power, because it succeeds in imposing themes and an aggressive political language. Migration, internal security, national identity, and the “protection of domestic workers” push aside questions of growth, productivity, and long-term investment. Elections in Sweden, Latvia, and Denmark in the fall, as well as in Hungary and Slovenia in the spring, will further reinforce this trend. The common denominator is not a shared ideology, but the absence of a vision.

Serbia enters 2026 in a familiar state of permanent political uncertainty and continuous campaigning by those in power. Elections are always “on the horizon,” especially when they have not been formally called. Arrogance, pressure, and violence become political methods, while ignoring and demonizing dissenters turns into a standard pattern of behavior. Foreign policy remains a balancing act without a clear direction, while domestic politics is reduced to managing crisis as a permanent condition. Young people are leaving, while labor is quietly imported, without strategy or serious public debate.

ENTITLEMENT AND XENOPHOBIA

One of the key issues of the coming years will be population movement. It is already happening on a large scale, but not smoothly. People from Africa and Asia are moving toward Europe and North America. Climate change, demographics, and inequality push them forward, while potential “host” countries tighten laws and erect physical and administrative barriers, creating mutual resentment between natives and newcomers. On one side are the “threatened professionals” unwilling to do hard jobs, blaming unfortunate people who are present yet invisible—workers without rights, residents without a sense of belonging. In this context, a dangerous thesis emerges: that new economic migration could become a potential “internal army” under state control. And so, while political elites announce tougher immigration policies, the economies of those same countries grow ever more dependent on imported labor. Construction, agriculture, logistics, healthcare, elder care, delivery services, and hospitality could not function without migrants. The problem is that this dependence is concealed, while political capital is built on the promise that migration will be “brought under control.”

In practice, this produces a new social layer: people who work but are not accepted; who pay taxes but have no political voice. They live in developed countries but are not considered part of society. As the number of migrants grows, so does xenophobia. It is not always racism, but fear—fear of losing jobs, identity, and social security. In societies where the middle class is weakening, immigrants become the easiest target. Politics exploits this, and the right does not need to offer solutions—it is enough to point to a culprit.

The problem of the middle class is not only economic, but political and identity-based. Over the past fifty years, Western societies functioned on an unspoken deal: education, work, and loyalty to the system would guarantee relative security. That carefully cultivated system is falling apart. The middle class is losing not only purchasing power, but a sense of purpose. Jobs become temporary, contracts shorter, careers fragmented, and social status unstable. This is the moment when economic pressure turns into a political stance. Unlike the poorest layers, the middle class has something to lose, while lacking the elite’s capacity to insulate itself from the consequences of change. Precisely for this reason, it becomes the most politically unstable segment of society—its frustration articulated not through demands for systemic reform, but through resistance to changes perceived as threats. Immigrants, globalization, and technology merge into the same vortex of lost control.

The impact of immigration on unemployment is often misrepresented. In the short term, migrants generally do not “take” jobs from the local population; they fill positions that local workers no longer wish to perform under existing conditions. In the long run, however, an excess of cheap labor negatively affects wages and workers’ rights. Employers have little incentive to improve working conditions if there is always a new contingent of people ready to work more for less.

THE WORKING CLASS GOES TO HEAVEN

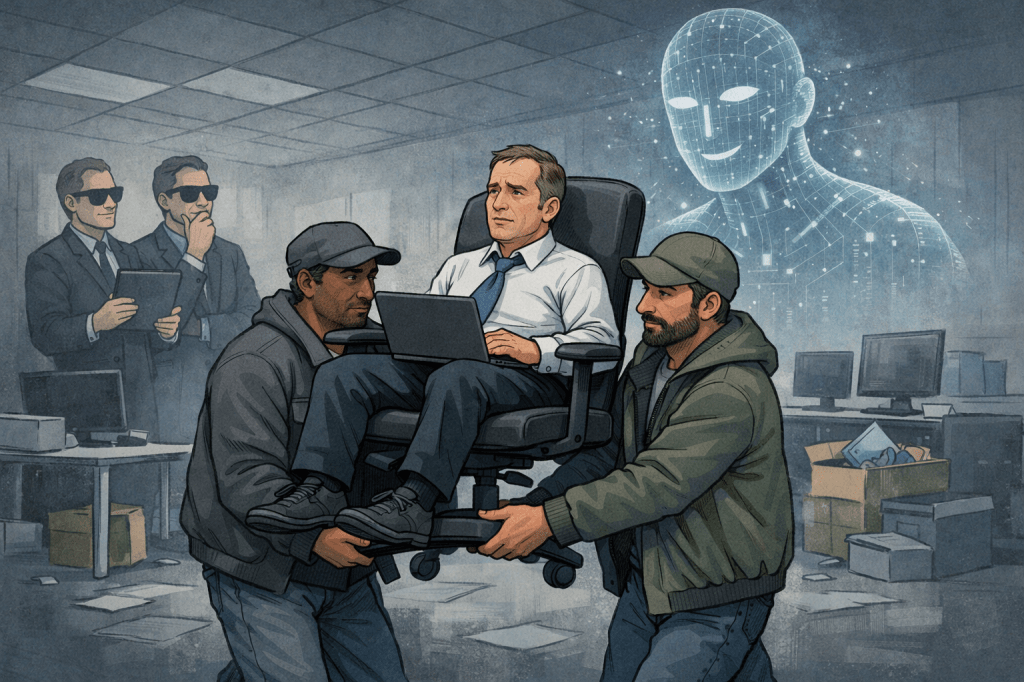

To the issue of “newcomers,” artificial intelligence has been skillfully attached. AI does not replace migrants, but the domestic middle class. Administration, accounting, analytics, parts of education, media, and legal services are losing the scale they once had. Migrants take over physically demanding jobs, algorithms handle office work, while a small number of highly positioned individuals remain untouched. Between these two poles remains a growing number of formally educated people without stable positions in the labor market. Thus arises a double pressure and fertile ground for political radicalization, accompanied by the omnipresent narrative of “migrants out.” If these trends continue, population movement will become not only an economic issue, but also a security and political one. In 2026, immigration will not stop, but the illusion that the problem can be ignored or solved with demagoguery and slogans will disappear.

Artificial intelligence is still treated in public discourse as a technological issue, even though its real scope is deeply political. The problem is not its existence, but who decides where it is applied, whom it replaces, and who bears the consequences. In the current system, the gains from automation end up in private hands, while the risks fall on the rest of society. Companies increase productivity and profit, while society faces insecurity, retraining, and growing distrust in institutions. Unlike previous technological waves, artificial intelligence does not require the mass employment of new workers. It does not create a new middle class; it rationalizes the existing one. That is precisely where its political danger lies. A system that for decades promised the labor market would absorb unemployment is now, for the first time, left without a credible answer.

Historically, major technological changes brought fear and resistance, but also a new balance. The Industrial Revolution destroyed the old world of craftsmen, but created the welfare state and labor rights. Computerization eliminated many professions, but created a new middle class. Artificial intelligence, for the first time, takes over not only physical labor, but also cognitive tasks, decision-making, and analysis—at a speed that leaves no room for institutional adaptation. If these trends continue, AI will not produce mass unemployment in the classical sense, but mass insecurity.

2026 AS A YEAR OF NO RETURN

When all these themes are viewed together—elections, immigration, the rise of the right, artificial intelligence, and the breakdown of the labor market—it becomes clear that 2026, even without dramatic upheavals, will be a year of exposure and confirmation that the contemporary world has fundamentally changed. The powerful will continue to line their pockets, politicians will taste the stew they themselves have over-seasoned, while ordinary people will adapt to new conditions. After all, we can agree—it can always get worse.

The strengthening of the right in the United States and Europe is not merely an ideological shift; it is a response to a society in which insecurity is growing and trust is declining. Conservatives do not offer solutions to the structural problems of the labor market, immigration, and technology, but they do offer a sense of control. Borders are visible; algorithms are not. Migrants have faces; the system does not. The right does not need to win everywhere to shape politics—it is enough to impose themes and narratives that are then adopted even by more liberal governments. In this way, political space narrows further, and conflict becomes normalized as a mode of governing society.

The year 2026 clearly shows that there is no return to the old normal. The direction forward remains uncertain, but it is evident that the political, economic, and social patterns on which stability once rested have been exhausted. Elections will be held, governments will change, and systems will continue to function, while the space for real decisions continues to shrink. Societies are entering a phase in which politics deals with consequences rather than causes, and in which there is neither time nor political space left for thoughtful long-term solutions. Though, as we said in the previous paragraph—it can always get worse.

Leave a comment