Order in the Chaos of Routine

There comes a moment in life when a person realizes they no longer wish to change their habits, because those habits long ago ceased to be small rituals and have turned into the structure of their everyday life. After sixty, it’s no longer the adrenaline of new beginnings that moves us, but the serenity of a familiar rhythm. What we once did on a whim, by chance or out of impulse, now becomes an essential part of the day. Habits are like architecture: they build walls that make us feel safe and open windows through which we already know what we will see. With age, rituals stop being charming little quirks and become our mental compass—or, as the younger would say, our GPS. It’s the best way to cope with a world growing more chaotic by the day.

And so, every time I land in Serbia, everything unfolds in the same order. I unpack my suitcase and push it under the bed in a room that hasn’t been mine for years but still smells like childhood. No matter how often I promise myself to “improvise a little this time,” I end up doing exactly the same.

Bakery, tavern, bookstore…

First—the bakery. Not just any, but the one where pastries are still measured by sight, not by scale, and where the rolls are so good that only the French ones come close. That’s where the first conversations with strangers begin—about the weather, politics, rising prices. In that brief ritual, while waiting in line, every year of distance between me and the city disappears as if it never existed.

Next comes Stara Srbija, the tavern that looks exactly as it did twenty years ago: the same stain on the wall, the same smell of cooked meals, smoke, and alcohol. There I meet old colleagues I haven’t seen since my last visit. The conversations are the same but no less dear—grandchildren, sports, nostalgia, who won the NIN Award this year. After two hours, I haven’t learned anything new, but I’ve recharged with familiar warmth.

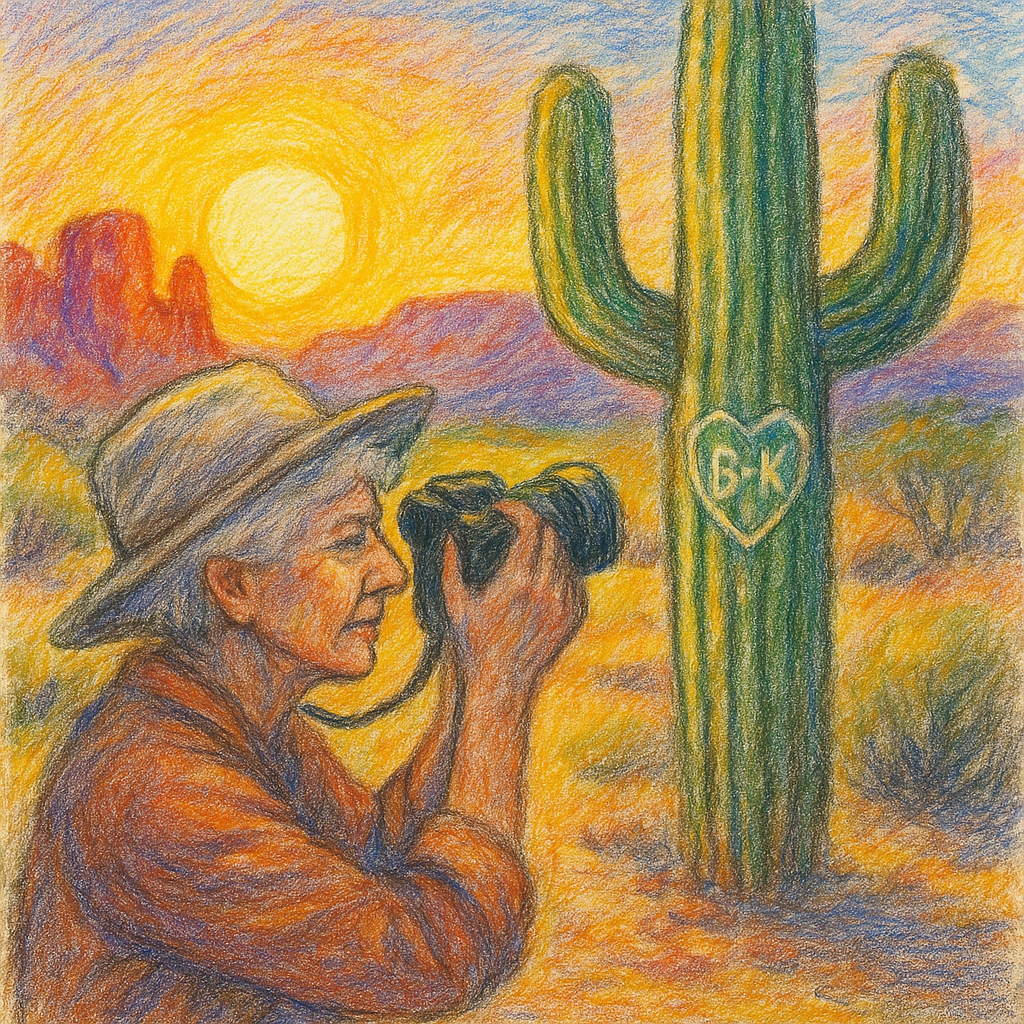

The next stop is the Laguna bookstore. I browse the shelves, leaf through the books, and buy a few titles I’ll, as always, not read until I’m back in Arizona. I don’t know why, but in American silence, it feels best to read what I brought from Serbia.

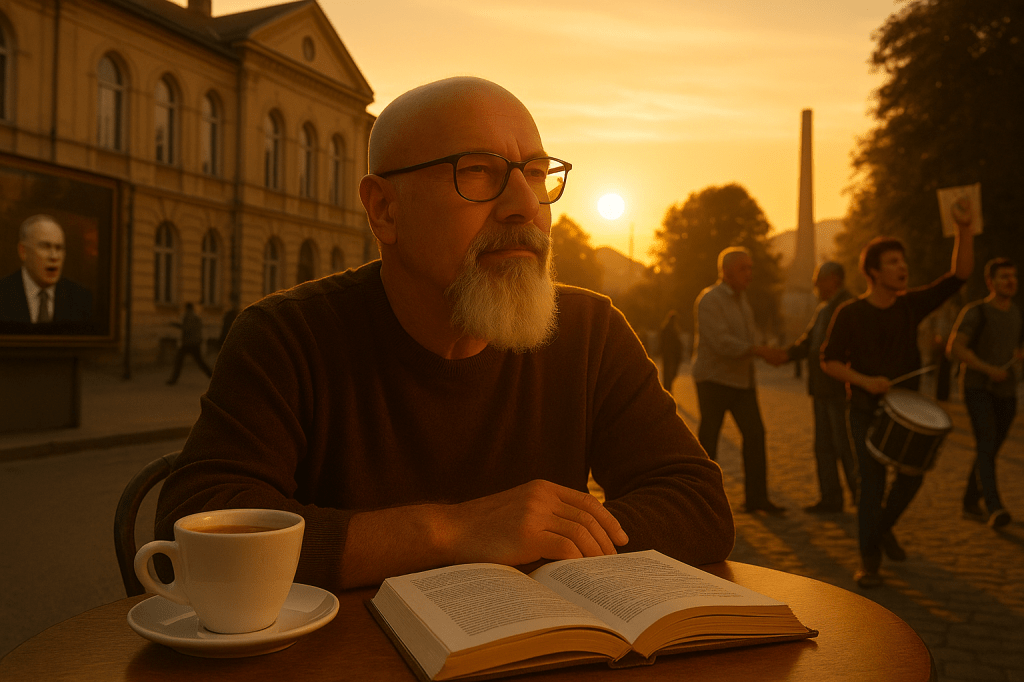

And then, when the city quiets down and retreats into its evening routine, when the lights go out and I return home, begins that time of day reserved for old books. On the shelf in the living room, about fifty titles await me—survivors of all the moves, renovations, and “rational decluttering.” I always pick one at random, and it becomes my companion throughout my brief stay in my hometown. This time I “grabbed” Tolstoy’s Notes of a Madman. I read it slowly, a few pages each night, the way one drinks Turkish coffee—with relish, unhurried, savoring every sense. While the TV hums in the background about “historic speeches” and “decisive negotiations,” I stumble upon lines like this:

“Today they took me to the provincial office for observation, and opinions were divided. They decided I was not insane, only because I tried my best not to give myself away. I didn’t, because I fear the asylum; I fear they’ll prevent me there from pursuing my mad work. They concluded I’m prone to emotions and something of the sort, but otherwise of sound mind.”

The next day—my walk. First through the park, the same one where more than half a century ago I chased a ball. Now I walk slowly, stopping by the same benches and trees. I always meet someone there: a schoolmate, a former colleague, a cousin who’s aged faster than I have. The conversations are short and always alike—health, children, America.

My path almost always leads me farther, to Šumarice, where history and silence touch. As I walk through the woods, time itself seems to move slower. In the evening, I wander aimlessly through the city center, recognizing faces in my imagination as if we had grown up together. Taxi drivers argue about politics, a chestnut vendor and a pensioner debate world affairs as if they were headed to a UN Security Council meeting the next morning. I shrug, return home, pick up the book, and turn the page:

“Until I was thirty-five, I lived like everyone else, and nothing peculiar could be noticed about me. Such things happened to me only in early childhood, up to the age of ten, and even then only in fits, not constantly as now.”

Meetings with friends are usually short and on weekdays. Everyone has their own life, family, and weekend plans. Our encounters are brief, spontaneous, and sincere. We meet, talk about everything and nothing. No one tries to sound profound—we leave that to those sitting in TV studios explaining the world. And Tolstoy, after all, still has the final word:

“I remember, once I was getting ready for bed, I was five or six. My nurse, Yevpraksia—a tall, thin woman in a brown dress, with a cap on her head and loose skin under her chin—undressed me and put me in bed. ‘I’ll do it myself,’ I said, climbing over the railing. ‘Come now, Feodyenka, see how good Mitya is—he’s already asleep,’ she said, nodding toward my brother. I jumped into bed, still holding her hand. Then I let go, kicked my legs under the blanket, and tucked myself in. It felt so wonderful.”

Photographs, drums, optimism…

One afternoon, instead of following my usual route, I stopped by the city gallery for an exhibition dedicated to student protests. The place was packed: high-schoolers with backpacks, professors with serious faces, parents of the “children” in the photos. I watched a couple, holding hands, moving from photo to photo, searching for their son’s face. “He’s here somewhere, I’m sure he is,” the woman kept saying, pausing before every frame. They didn’t find him in the pictures, but they did in a student message pinned to the wall:

“For those who can’t be with us—thank you for teaching us to believe that we can.”

The rhythm of drums coming from the corner filled the room, along with a quiet sense of optimism. At home, on the nightstand, my book awaited:

“Like all mentally sound boys of my time, I went to grammar school, then to university, where I graduated from law.”

One morning, while I sat on a park bench, an old schoolmate approached. We hadn’t seen each other in years. “You know I lost my house?” he said immediately. “A fast-track bailiff decision. Sold it over an unpaid electricity bill—seventy-four thousand dinars.”

He paused, then added, “You know, Serbia must be the only country in the world where you can’t be sure you’ll live if you fall ill, work if you’re honest, or reach retirement if you’re diligent. But one thing is certain—you will pay your bill!”

When I got home, I opened my book where I had stopped the night before. I read aloud, as if trying to understand a world where someone loses a home over a bill, while others still strive to ‘wisely increase their wealth’:

“My wife and I had saved money from her inheritance and my convictions about redemption and decided to buy an estate. I was unusually interested in increasing our property—as one should be—and particularly in doing so wisely, better than others…”

Days passed. Instead of walking the same paths, I spent most afternoons at a café in front of my old high school. That’s where I meet friends from youth. Someone always drops by—a history teacher counting days to retirement, a classmate who says nothing has changed except that we now wear glasses and talk softer. In that mix of planned meetings and accidental encounters, there’s a kind of comfort. In a world teetering on the edge of a nervous breakdown, my little routines still feel like proof that sanity hasn’t completely vanished.

And then inevitably, it’s time to return to America. I pack my habits and rituals along with my belongings, carefully placing them between souvenirs and the books from Laguna that, as always, wait their turn to be opened on the other side of the ocean.

On the plane—an unexpected scene. A few rows ahead sits a group of Belgrade high-school seniors. Twenty or so boys and girls, bright-faced, polite, well-mannered. At first, I thought they were athletes—but no, they were invited to visit the United Nations. Some are flying for the first time, some leaving Serbia for the first time, but all speak of the trip with a seriousness and respect rarely seen today. One girl said she wanted to become a diplomat “to represent Serbia the right way.”

Watching them, I realized that this generation carries within it something we older ones may have long lost: the belief that the world is not only a place to survive, but a place to improve. And right there, between clouds and the ocean, I asked myself: does Serbia deserve such a generation—decent, curious, ready to listen and understand even those they disagree with? And, perhaps even more—do the United Nations deserve such visitors, young people who still believe that once-prestigious institution can be something more than a stage for endless speeches and diplomatic clichés?

I arrive home, where the woman of my life awaits—with a new layout. She’s moved the plates in the kitchen, rearranged the wardrobes in the bedroom, and the shelves in the bathroom. It will take me at least a week to find my way again—maybe a month. Because old habits, after all, are not easily abandoned.

MAY WE LIVE AND BE WELL

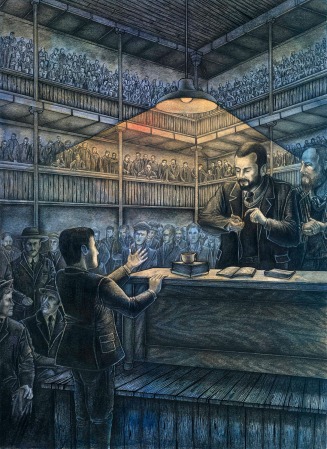

Sarajevo, January 1914.

Vukašin, a merchant in Baščaršija, sat with his morning coffe and leafed through the papers. On the front page: news of the Balkan Wars, a new model of French airplane, the British kingdom and industrial strikes. Near the bottom—strained relations between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. Vukašin read, sighed, and said aloud:

“War? Ah, no one’s that crazy.”

That afternoon he received a shipment of new goods and scolded his assistant for mixing up the stock. In the evening he ate sarma with his family. On Wednesday he sat with neighbors in the tavern; on Thursday he delivered groceries to Mrs. Wagner…

On June 28, 1914, he went to the market. He heard gunshots. Someone said, “They’ve killed Franz Ferdinand.” He shrugged and thought, “Surely there won’t be another slaughter over one man…”

A month later, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia—as if someone had merely been waiting for a pretext and everything else had long been ready. And Vukašin, like millions of others, had no inkling that the shot that morning had awakened the beast. Until then, everyone had lived their small lives in peace—planning, working, waiting. No one wanted war. No one asked for it. And when it came—they were astonished.

Gavrilo Princip pulled the trigger and the rest was a chain reaction. Vienna wanted revenge, Berlin gave support, Petrograd muttered, “Don’t touch our brothers.” Paris stood by its allies, and Europe stepped to the edge and jumped into the abyss. One bullet in Sarajevo, then a month of ominous silence while armies mobilized and ultimatums were drafted… Propaganda at the time was less subtle, but present, brutal, and effective. Patriotism, hatred of the enemy, faith in king or state were its main lines. On the posters, the enemy was a beast and our soldier a hero. Censorship was used in all countries to prevent defeatism and the spread of “unsuitable” information. Churches, schools, and military institutions took the lead in shaping the public narrative.

The world plunged headlong into war. Everyone believed they’d be home by Christmas. No one imagined four years of hell, the likes of which had never been seen.

Berlin, February 1933.

Otto, a tool-factory worker, took off his greasy apron and ate a half-empty sandwich in the back of the shop. With his colleagues he talked about everything and nothing: the price of milk, class differences, army maneuvers… They concluded it couldn’t go on like this. One said the communists should take matters in hand. Another waved him off: “You’d be happy about that, would you?” Otto kept quiet. He believed neither side. What mattered most was to be left alone and peacefully await the next paycheck.

The next morning the Reichstag burned. The Nazis blamed the communists. A state of emergency was declared and civil rights suspended. Many rejoiced: “At last there’ll be order.” Otto wondered how everything could change overnight. He kept quiet, didn’t make waves. He drew many more paychecks—and then came the uniform, training, oath… War.

How did the world breathe before it suffocated? On the surface—calm and normal. In Paris they spoke of fashion, exhibitions, and scandals. In Belgrade—taxes, harvests, and how the king was too hard-line. In London—markets, colonies, a convoy bound for India. In New York—the new Ford plant, the price of tobacco, yet another ship of immigrants docking. Everything followed its course. Trains flew by, telegraphs chirped, industry clattered without pause. People made plans and bought their first summer clothes. Wrote love letters, prepared weddings, bought cradles… Beneath the veneer of normality, pressure built. Factories saw strikes. Parliaments broke their lances deciding which side to lean toward. In the villages, people mostly kept silent—they knew nothing good comes when the German gets riled.

In Vienna the elite feared disintegration. In Berlin the generals studied maps and drew borders. In Moscow the communists discovered that ruling isn’t easy—you have to feed the people—so they found salvation in an external enemy. In Paris, conformism beat every other “-ism.” The French weren’t much in the mood for war. From London came the message that the new division of the world was, in fact, a matter of honor. In Serbia—pride, stubbornness, and a wound still bleeding from the Balkan Wars. Workers made policy, peasants worked, students dreamed of revolution. Markets haggled, taverns drank, theaters laughed, factories sweated. And no one—absolutely no one—suspected that in a month the whole world would look like an open wound without a bandage. The world walked on ice already cracking. It only took someone to stomp harder, one army to move and shout: “Charge!”

War propaganda became a science. In Germany, a Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda was formed. The goal wasn’t to inform but to shape. People ignored the persecution of Jews—not for lack of warning signs, but because no one wished to see them. Camps already existed and violence had gone public. Kristallnacht (1938) unfolded before the people’s eyes. Yet the world looked away, calling it “Germany’s internal affair.” The problem wasn’t a lack of information, but a surplus of propaganda, false optimism, selective attention, and collective fatigue.

In 1938 Hitler swallowed Austria. The world was silent. September: the Munich Agreement dismembered Czechoslovakia. Otto was sent to the border. “You know,” he told a comrade in the trench, “I can’t say I support war—but someone’s got to defend the nation.”

Dallas, 2025.

Tyler is 38. Drives a Ford, carries a handgun, believes the state shouldn’t meddle in his life. He dislikes taxes and “woke culture.” He supports Trump: “Not perfect, but at least I know where he stands.” He doesn’t trust liberal media; he follows conservative podcasts, Twitter, and listens to Joe Rogan. The war in Ukraine? “Not our problem.” Gaza? “They asked for it.” Inflation, the Chinese, migrants—all symptoms of American decline. Then, an assassination: Charlie Kirk is killed at a public event. The internet is ablaze. Theories. Counter-theories. The right calls for civil war. The left demands gun-control laws. TV programs critical of the authorities are banned. One by one, U.S. states teeter on the edge of emergency rule. Tyler tells his wife: “This doesn’t smell good.” Remote in hand, FOX News on the screen, he looks out the window. The street is calm. For now.

Over the last hundred years the world has turned on its head, but human naiveté, the greed of the powerful, and our urge toward self-destruction remain constants. In the first quarter of the first tenth of the twenty-first century, we enjoy the sweet idleness of the internet, bicker on social media, and play with artificial intelligence. Technology is everywhere. In Western Europe and America, wars are waged via keyboard; in Ukraine with drones; in Gaza with all means available to meet the daily quota of death.

Tyler has bought a semi-automatic rifle.

Everything Has Changed—and Everyone Has Swapped Places

In the First and Second World Wars reality was stark and the aggressors had names—Germany, Austria, Italy, Japan… The defenders of the world rallied under the banners of the Soviet Union, America, and Great Britain. Millions of civilians perished, and the victims were recognizable—above all the Jews, the most persecuted people. It was believed that after 1945 the world had learned its lesson and that the lines between good and evil were at least somewhat clearer. We hoped the chapters on camps, city bombings, expulsions, and racial hatred would never be reopened. But today the deck is completely reshuffled, and the world seems to have forgotten the recent past and its own blueprint.

Germany, Austria, Italy, Japan—countries that once shoved the world into war—are now among the most prudent powers. Their militaries are modest; their foreign policies measured. Germany is bound to the EU, Italy minds its own house, and Japan, though strong, rarely raises its voice. Maybe it’s guilt, maybe fear… Whatever the reason, one thing is certain: the aggressors of two world wars now play a relatively decent role in a planetary tragedy of wailing and gunfire.

At the same time, yesterday’s “good guys,” the protectors of the free world in the first half of the last century, have become engines of chaos. The U.S. and Russia, once united against fascism, are now in constant conflict—mostly with others, often with themselves. Russia, in “self-defense,” attacked Ukraine, borrowing the rhetoric of 1939. Under the threadbare banner of human rights, America left ruins wherever it wished to “help.” Guided by democratic principles, twentieth-century wars were waged against tyranny; today they serve as cover for invasions, coups, and the foulest colonial grabs.

No great power sits for a moral exam anymore; each calculates instead: how profitable is aggression, how valuable an ally, how long the public’s attention will last. While today’s empires negotiate feebly (and act far more lethally), yesterday’s victims have too easily accepted the role of executioner. Petty bullies in the Middle East, backed by big brothers in the West, are carrying out an unprecedented slaughter in the Gaza Strip. The Jewish people—symbol of twentieth-century suffering—through the policy of the Israeli state are conducting the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian people. In Gaza’s daily abuse of civilians, it isn’t only Hamas who die—children, refugee camps, schools—an entire enclave of sacrificial civilians is destroyed. The “democratic” world that once screamed “Genocide—never again!” now whispers “It’s complicated,” and does nothing to stop further war crimes. This is no longer a mere moral dilemma; it is the moment when historical roles have been fully reversed. Recent aggressors are disciplined, quiet, restrained. Former defenders have lost their compass and wage endless wars. Yesterday’s victims surpass their former persecutors. We believed that after 1945 we could tell black from white. Today there are only sides—ours and theirs—though neither is just. Law has become relative, morality overnight a luxury, and politics a small coin for settling the accounts of insecure, senescent men.

Leadership is no longer grounded in truth but in interest. If you have power—you’re right. And vice versa. And so today’s world irresistibly recalls 1939: marches in Washington, Moscow, even New Belgrade. But it also looks like 1914: a heap of local crises, armies at borders, politicians shaking poisonous draughts while citizens are convinced “there’s still time.” Everyone assumes someone else will pull the brake. And the runaway train thunders toward the ravine.

World War III may not break out this year, or the next—perhaps never. But if it comes, it won’t arrive as a surprise; it will be the consequence of what we’re living through now. When we one day look back from some trench, we won’t be able to say we didn’t know. We knew—but didn’t want to face the truth.

Ah well—leave it be. May we live and be well.

THE ANATOMY OF MEDIA PROPAGANDA

FROM BROKEN EGGS TO GLOBAL CATASTROPHE

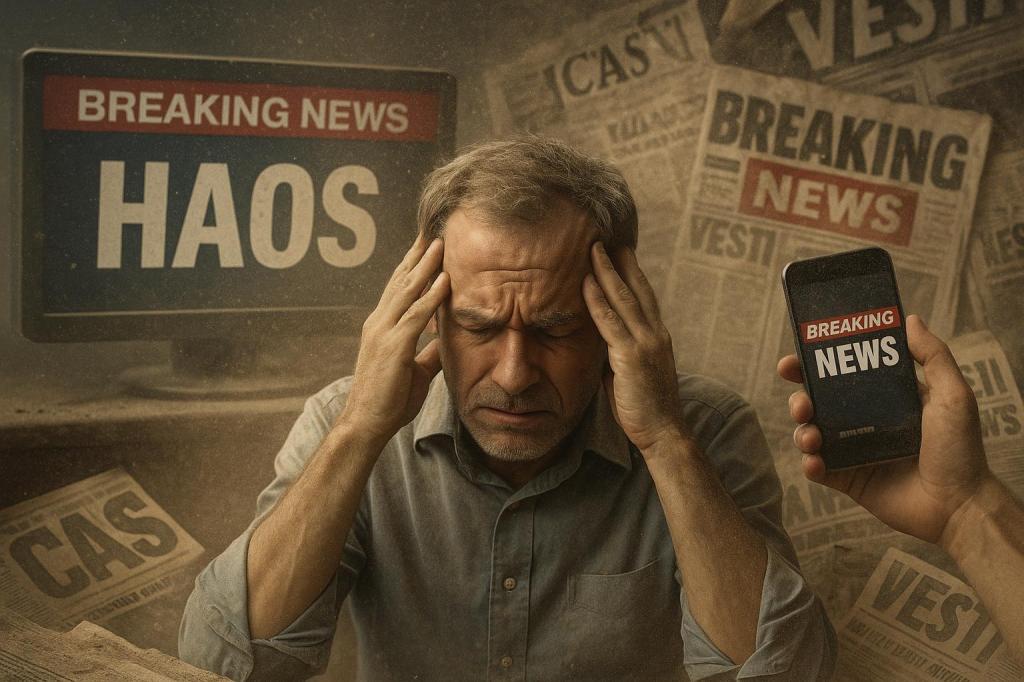

During a guest appearance on a morning talk show, a well-known psychologist shared a story: one of his patients said, “Doctor, I read the news ten hours a day and I feel like the world is ending tomorrow. Is that normal?”

The doctor replied: “It’s not normal to read the news ten hours a day — but it is normal to feel like the world is ending.”

Never in history have we been exposed to as much information pressure as today. If the old saying once held that “you can’t have too much knowledge,” it now turns out that too much information can shake both body and mind.

In an ideal world, every reader, viewer, or listener would process, analyze, and shelf every piece of content into their personal experience. But in reality, the day is too short, and the avalanche of data is relentless. News stories cascade one after another. When a new topic hits, the old ones don’t disappear — they recycle and pile up in our consciousness. Like grime on a window we can no longer see through.

Every outlet invents a new drama, offers a bigger threat, creates more panic. In our effort to stay informed, we become prisoners of our own curiosity. Inner peace vanishes, replaced by a constant state of alertness: war is about to erupt, and global catastrophe seems inevitable.

We interrupt this program — reason and logic have gone missing!

Journalism has changed. Once a pillar of public interest, a tool in the pursuit of truth, a foundation of an informed society — today, it has become its own opposite: an attention industry. News is no longer grounded in verified truth, but in screen time and click counts.

Ratings matter more than credibility. Speed trumps accuracy. Sensation beats context.

Objectivity has faded, and analytical journalism has been reduced to the work of a few brave, systematically sidelined investigative reporters.

And the audience? Far from innocent — devouring every sensational headline the tabloids serve. If there’s no blood, fire, tears, or victims — the story goes unnoticed. “Breaking News!” is every newsroom’s daily prayer.

In Serbia, headlines read:

“Grandpa stabbed over broken eggs.”

“A mother’s boundless love: ‘I want my son to die before I do’ — tabloids in tears, son in shock!”

In the U.S.:

“Sunflower allegedly looks like the president – mystery shakes midwest farm!”

“Wall Street panic: Analyst forgets password — stocks plummet!”

“White House insider claims president dozed off during online NATO meeting!”

Globally:

“Exclusive: Putin seen feeding pigeons – what does this mean for global stability?”

“Drivers shocked as giant penis-shaped sign reappears at roundabout!”

“Panda refuses bamboo – Asian diplomacy in crisis!”

Everything is urgent. Everything matters. No one asks: is it true?

Half of these headlines are real. The other half are made up.

Can you tell which is which?

After multiple propaganda “climaxes,” timed perfectly for prime time, comes a short break — a false peace — before news therapists reload the next round of informational ammunition.

If we switch metaphors — from sex to war — we could compare it to artillery: the barrage briefly stops, the barrels cool, and then it all starts again. In that silence, there’s no reflection, no real analysis — just a pause to recharge for the next wave of fear.

Propaganda First, Then the Bombs

Wars have always been fertile ground for sensationalism. Every bullet is preceded by a barrage of weaponized words. First comes propaganda — turning people into obedient herds — followed by media shepherds, leading them “down the right path.”

On one channel, Ukraine is a symbol of freedom. On another, Zelensky is a Western puppet.

One says Israel is a victim. Another calls it a genocidal regime.

In both cases, truth is buried under a mountain of bias, algorithms, and political interests.

When objectivity disappears, everyone picks the version of reality that suits them best:

“My facts.” “My source.” “My truth.”

Disoriented and distrustful, the public flees to social media — only to get lost in an even denser jungle: conspiracy theories, half-truths, fake news that spreads faster than it can ever be fact-checked.

And so, in this whirlwind of disinformation, people retreat into their own mental refugee camps — spaces where no one is trusted anymore.

Media Inflation

Psychologists already have a term for it: doomscrolling.

Endless, compulsive scrolling through destructive content. The digital equivalent of picking at a wound — you know it hurts, but you can’t stop.

The brain craves the next dose of anxiety. Fear is the cheapest drug of the digital age.

The cycle continues: stress triggers a search for news, and news creates more stress.

People wake up tired, go to work fractured, and fall asleep depressed.

Insomnia turns into anxiety. Focus becomes fragmented.

Social media algorithms shatter attention spans and herd us into echo chambers.

In these tribes, truth is irrelevant — only confirmation of our biases matters. Each tribe has its own borders, sources, prophets, and slogans.

Instead of dialogue: tribal war in the comments section.

And so we have digital “brotherhoods,” whose members, miles apart, fight endless battles from behind their keyboards — convinced they’re defending justice, unaware they’re only feeding algorithms that make someone else rich.

This well-oiled mechanism produces digital saturation with imagined truths.

The human brain, bombarded by lies and half-truths, loses the ability to tell important from trivial.

Child killings and celebrity breakups appear side-by-side.

Climate change and reality TV — equally weighted.

In this noise of nonsense, truth becomes irrelevant, and the audience unknowingly helps maintain the media circus.

Sensation Is the New Standard

In today’s media madhouse, even the murder of a previously unknown man — who suddenly became a conservative influencer — can dominate global headlines.

“Charlie Kirk’s murder sets the world on fire!”

“Tragic death of conservative hero sparks wave of violence in U.S.!”

“U.S. revokes visas for those who didn’t mourn Charlie Kirk!”

The headlines never stop.

TV channels interrupt programming.

Online debates erupt.

Flags are lowered. Commemorations held. Presidents express condolences — as if a statesman of historic importance had fallen, not just an influencer riding the wave of algorithmic fame.

This single, irrational act of violence gets more media attention than the escalation of war in Gaza, mass protests across Europe, or even the death of Robert Redford.

Logic collapses. One inflated name outshines events of real, far-reaching consequence.

The world no longer measures the weight of news by its impact — but by its virality.

Tragedy becomes spectacle.

And spectacle is the most stable currency in public discourse.

What’s Left for the Ordinary Person?

What can the average person — the news consumer, the reader, the viewer — do?

Perhaps the simplest thing. But also the hardest:

Turn away from the screen.

Go for a walk.

Read a book.

Have coffee with a friend. Listen when they talk.

Do whatever reminds you that reality is still here — firm, living, and waiting for us to return.

That doesn’t mean abandoning the world of information. It means practicing selective intake.

Just as we don’t eat everything we’re served, we shouldn’t swallow every headline tossed at us.

The first step to healing is an informational diet.

After that comes context — and truth never lives in the headline. It demands patience, deep analysis, investigative reporting, documentaries, books.

Things that require time — not just a click.

And finally, we must accept that we can’t change most of today’s headlines.

Instead of panicking, we must protect our mental health.

Not by closing our eyes to reality — but by refusing to let it destroy us.

We Only Have One Life

Because life, as the poet said, is just this one — there’s nothing beyond it.

If we spend it endlessly scrolling through the latest “breaking news,” we’ll waste it in a tunnel of media deception, blinded by the glow of fake spotlights.

So maybe the wisest move is the most obvious:

Don’t read more. Don’t read less.

Read smarter.

Learn to spot the difference between news and propaganda, between information and manipulation, between what matters and what doesn’t.

If we can do that, maybe we’ll regain what this media madness has stolen —

clarity of thought and peace of mind.

A decade ago, anyone glued to the news all day would be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and prescribed medication. Today? That’s just the statistical average.

Humanity has turned into one giant therapy group, where we all say in unison:

“Just one more headline… one more news panel… one more reality show… one more staff meeting… and then I’ll stop!”

In a world where thinking the world might end tomorrow feels normal —

maybe the only real act of sanity is this: to stay calm, stay human, and keep smiling.

And when the world does finally collapse — rest assured —

the tabloids will break the story first.

Prime time.

Exclusive.

Just for you.

THE PARDONING OF INJUSTICE

On the Brioni islands, in the summer of 1978, Josip Broz showed U.S. President Jimmy Carter an ancient olive grove that had outlived invaders, regimes, and systems. The seasoned statesman told his younger colleague: “Trees endure for centuries, politicians only until the end of their term.” Malicious tongues would add that it’s easy for Tito to preach about the transience of power when he was elected lifetime president of the SFRY. The most famous peanut farmer from the state of Georgia soon felt for himself the difference between the people’s permanence and power’s impermanence. Three decades later, in Prague, there was another meeting between a “leader of the free world” and a president from the Balkans. Obama and Tadić didn’t discuss gardening, but they did touch on basketball. “Our players are getting close in quality to the NBA pros!” Boris boasted. “And imagine what kind of basketball power you’d have if you hadn’t broken up Yugoslavia!” Barack shot back, side-eyeing Angela Merkel. “Summits” also marked the reigns of later Serbian presidents, but more on them another time in the column “Comedy, Misery, Disgrace!”

“IF YOU’RE A PORK CHOP, YOU’RE NOT FOR SAUSAGES”

Although at first glance they seemed to have done a decent job, history was harsh to the politicians just mentioned. While he was alive, Broz was exalted to the stars, only to become overnight the whipping boy for all the frustrations of Joža’s heirs. Carter, Obama, and Tadić became hated, not so much for personal failures as for the fact that they came to symbolize citizens’ disappointment in their own unrealistic expectations. Carter was criticized for lacking courage and decisiveness—even though he pioneered putting human rights at the center of U.S. policy. Obama was blamed for everything under the sun—though he led America out of one of the greatest economic crises in its history. The hatred of the first “colored” president has little to do with policy and much to do with the personal complexes of no small number of racists in the U.S. Boris Tadić was attacked from both left and right, though during his term Serbia was closest to Europe, and civil liberties and living standards were at their highest since the days when Serbs said a resounding “no” to Ante Marković’s policies. It should also be said that each of the above presidents was mentally stable, with no visible personality disorders. Unfortunately, back in vogue came those quickest to pounce when the doors of the world’s madhouse swung ajar and when democracy, living standards, and basic normalcy disappeared from most citizens’ list of priorities. Thus, in America, “normal” politicians were replaced by Republicans Reagan and Trump; in Serbia, by Radicals Nikolić and Vučić.

In search of a strong hand, both Americans and Serbs turned their backs on those who respected the constitution and advocated compromise and dialogue. Both got, alas, the most extreme version of the politics they voted for—only to find themselves in a deep democratic crisis. Civil liberties are slowly vanishing, institutions have lost their strength, and “firm-handed” leaders are ushering in autocracy. People quickly forgot the Brioni olive trees and the casual basketball banter from Prague, and “between two evils” they voted for dread and horror. By mid-2025, citizens of the U.S. and Serbia were feeling, intensely, the consequences of their own choices—choices that led to radicalization and the erosion of basic democratic standards. What used to be a debate over shades of difference has become a conflict marching toward the abolition of freedom and human rights.

After many years, America is now feeling on its own skin what it has lectured others about for decades. Summer days passed under the sign of protests against the deportation of thousands of immigrants. Images of police repression in the streets of Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, and Chicago read like the sad chronicle of a country where nothing is normal anymore: blocked streets, tear gas in the air, zip-ties on protesters’ wrists. Instead of dialogue, President Donald Trump sent military reservists first to California, then to the capital, where he deployed the National Guard around the Capitol. American media are still flailing in a net of imposed unanimity from on high, but Donald doesn’t worry: between The New York Times and The Washington Post, a Trump voter will opt for Instagram and TikTok.

The totalitarian rule of a single man has lasted far longer in Serbia, and its citizens have endured the consequences of their neutrality and “blank ballots” for thirteen years. When you shake popular champagne that long, it doesn’t take much for the cork to blast out of the bottle. In Serbia, however, something truly horrific happened: because of corruption and lawlessness, 16 innocent people lost their lives. After the tragedy in Novi Sad, an explosion of emotion and common sense sent people into the streets. Students and citizens demanded accountability, respect for the law, and functioning institutions. Instead of meeting those demands, Vučić leafed through the memoirs of his idols and forged a new tactic. In fascist Spain and later in Latin America, dictators were the first to understand that uniformed police often weren’t enough to crush popular revolt. So they hired civilian enforcers to intimidate, beat, and kill opponents. Under Franco they were called Falangists; Somoza in Nicaragua had his esbirros; Pinochet his brigadistas; Perón the Triple A. Many years later, in the heart of Europe, Vučić formed his “loyalists.” Men in black—most with criminal records—who, under the pretext of guarding party offices, pelt unarmed demonstrators with stun grenades, stones, frozen water bottles, and eggs. Meanwhile the police protect the criminals and arrest those who react to the thugs’ provocations.

PARDON ME, MR. PRESIDENT

If a lost Norwegian visiting Belgrade Waterfront or the Freedom Fair were to ask how it’s possible, in democratic countries, for criminals to attack unarmed citizens with iron rods and walk away unpunished, he’d get a simple answer: presidential pardon! In July and August 2025, Aleksandar Vučić pardoned several of his protégés accused of violence against students. Instead of defending the victims, the state sided with the perpetrators, erasing the line between justice and loyalty.

Donald Trump went a step further and, on Inauguration Day, issued mass pardons to participants in the January 6, 2021 attack on the Capitol. Sentences for members of extremist groups were drastically reduced, while thousands of other participants received permanent clemency for serious crimes. Thus ended the judicial epilogue to one of the fiercest assaults on American democracy: responsibility erased with a rubber, violence legitimated as part and parcel of political struggle by the privileged and the president’s bullies. At the moment, the president is reportedly toying with pardons for convicted pedophiles as well—but that’s another story.

In the play Balkan Spy, Danica Čvorović says at one point: “If they betrayed their wives, why wouldn’t they betray their country?” Applied to political mimicry in the U.S. and Serbia, we might freely say: whoever lies to their own citizens—no wonder they cheat their allies. Here begins the double game on Ukraine and the tragedy in Gaza. The “governorate” of Aca the Serb from Red Star’s north stand presents itself as a country with an independent foreign policy. Weapons and ammunition produced in Serbian factories end up in the hands of Ukrainian soldiers, while President Vučić insists Serbia will never impose sanctions on fraternal Russia. Public friendship with Moscow; secret trade with Kyiv; and the final paradox—Serbia profits from a war it officially condemns.

America, for its part, openly backs Ukraine with billions in military aid. Yet while telling the home front it stands in solidarity with embattled Ukrainians, behind closed doors it negotiates with Moscow—without its “protégé,” Zelensky, at the table. In mid-August, Vladimir Putin visited the United States. Donald played the clown as usual; Volodya’s knees buckled—not from fear, but from arthritis. They discussed a “peace plan” in which Ukrainian resources and territory served as bargaining chips for two great powers. Thus the word peace was, and remains, a diplomatic screen for a redistribution of interests.

The same story applies to the war in Gaza, where slogans about ceasefires and humanitarian aid scatter under the weight of weapons delivered to the aggressor. In the first six months of 2025, Serbia exported arms to Israel worth €55.5 million. Only when a UN special rapporteur publicly warned that international law was being violated did Serbia’s leadership react. The president announced a supposed halt in exports—only to, as usual, break his promise.

The U.S. went many steps further: in February it scrapped the law barring the use of American weapons where international humanitarian law would be violated—paving the way for arms shipments worth billions. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, America accounts for over 70 percent of global arms exports to Israel.

At the end of this masquerade, Serbia and America stand before the same mirror: preaching peace while exporting weapons; invoking democracy while crushing protests; promising a bright future while dragging citizens backward. Democracy wasn’t killed with one thunderous volley, but with a thousand small bullets of lies, backroom deals, and pardons for political thugs. If once great ideas and principles led nations forward, today we’re left with petty haggling over interests and the weighing of power. Serbia increasingly resembles Franco’s Spain; America, Mussolini’s Italy—while the citizens of both countries teeter between hope and despair.

The crisis of democracy is no longer an external threat; it’s becoming an internal metastasis. The question is no longer whether democracy will survive, but whether citizens will fight to win it back—someday.

September 6, 2025

It was Saturday, early morning, when customers discovered that Slava’s barbershop was closed. Next to the sign with working hours stood a short, bilingual message: “This Saturday, due to marital obligations, I will not be working!”

No, no—it’s not what you think, mischievous reader. This Arizona barber is an honest Serb with permanent residency in the U.S., who keeps intimacy behind closed doors. This was actually about tourism.

The last time Slava took his Stana on vacation was in 2012, through her union in Serbia. After that, they went a few times to the “Pumpkin Days” festival in Kikinda, where the biggest pumpkin is chosen, but since coming to Arizona—vacationing was forgotten. This weekend, they decided to visit the northern part of their new desert “homeland.”

After drinking his coffee, packing the trunk, and starting the Buick to cool the inside, Slava paced nervously down the hallway, waiting for his lifelong companion.

“Just five more minutes!” Stana called from the bathroom.

“Come on, woman, we’re going to the mountains—who’s going to look at you there? Your five minutes last as long as two Trump terms!”

As soon as they sat in the car, the barber adjusted the mirrors and hit the highway. Stana carefully typed the destination into her phone app, but Slava didn’t trust GPS.

“Some woman from a phone isn’t going to tell me where to turn. The best navigation system is a wise male head—and if you’ve got a map, even better…”

“But Slava, this ‘woman’ knows where Flagstaff is. Last time, you ended up toward Nogales when we wanted to go north.”

“That wasn’t a mistake—it was… an alternative route.”

He popped in a CD with the Yugonostalgic hits of his youth, they reached Ash Fork, where they joined the famous Route 66.

“On this road, my dear, Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper rode their motorcycles in Easy Rider!” he sighed wistfully.

“Don’t be biased—Thelma and Louise drove here too!” Stana snapped back.

After an hour and a half, they stopped for breakfast at the Monte Vista Hotel, famous for its mystical happenings and paranormal events. They stepped into a restaurant filled with the smell of bacon, coffee, and the Wild West. Everything was authentic, including staff that could scare any normal child. They sat at a table near the entrance, with a clear view of the reception desk where old Billy, a hundred years strong, dozed off.

Their waitress could have passed for a witch—messy hair, black makeup, and a tattoo of an evil spirit on her forearm.

“Good morning, what can I get you?”

Stana ordered a pastry with white coffee, Slava went for a full omelet and extra bacon—or, as the menu called it:

“One ‘Morning Apparition in a Vampire’s White Cloak’ and ‘The Sheriff’s Last Stand,’” the waitress summarized.

“I thought I was ordering breakfast, not a horror-western. But fine, I’ll take it before they change the genre and bring sushi!”

As Slava poured his third coffee, he thought he saw the bellboy and porter vanish through the western wall, where there were no doors or windows.

“Watch out for the Lady in White,” the waitress teased. “Sometimes she shows up after the third coffee.”

She confided in them that at a corner table often sat a pale man with long white hair, who came in every day, drank a bottle of red wine, and when the bill came—simply disappeared. They checked security cameras, but no trace of him until the next day. It had been like that for years.

“This place reminds me of the in-laws—you’re never alone, and you always end up paying for their drinks.”

“They say once a guest reported his chair dancing around the room,” Stana added.

“And when my customers steal newspapers, you all say Slava exaggerates!”

After breakfast, they continued to Sunset Crater, the volcano whose terrain resembles the surface of the Moon.

“See, Slava, Armstrong and the other astronauts trained here before flying to the Moon,” said Stana.

“So, they practiced walking on the Moon… in Arizona?”

“Yes, the terrain is similar.”

“Then I can claim I was in Egypt, because I walked on sand in Kikinda.”

“Hopeless case.”

“If they went to the Moon, then I fought in the Battle of Kosovo!”

That evening, they visited Lowell Observatory. The curator explained that Pluto had been discovered right there.

“So, little Johnny from Flagstaff peeks into a telescope and bam—a new planet. Like guessing the right rakija in a tavern—pure luck.”

When he heard Pluto was no longer a planet, Slava shrugged: “My buddy retired too, but we still call him Tika the Postman.”

They spent the night in a modest motel, free of mysteries. The next morning, as Stana was getting ready, Slava impatiently tapped his feet by the window:

“If you’re not ready in five minutes, we’ll get to Bisbee after the third mining shift is over.”

“There are no mines anymore, Slava.”

“That’s why we’re leaving early—to see what’s left.”

As they drove south, the landscape changed: pine trees gave way to rocks and desert, until finally the hills of Bisbee. The town’s entrance looked like an old postcard—brick facades, winding streets, and ruins where the copper mine once stood.

Their first stop was the Serbian Orthodox Church of St. Stefan Nemanja. An elderly man in a black cassock greeted them.

“Father Radovan,” the barber said warmly, “when I was a kid, I heard my great-grandfather—my namesake—worked as a miner in America. I’m curious if it was here in Bisbee.”

“We have a donor book from 1877, so if he was a man of faith…”

“But the church was founded only in 1956?” Stana asked.

“Among the miners, there was always a man of God, or a priest’s son. Services were held in homes. Here, look—there’s a Slavoljub, last name Števin?” Father Radovan said, leafing through the old book.

“That’s him! My namesake and distant ancestor, a tambura player. They say he sang in the mine when times were hard. He made it far by ship, and I barely dragged myself here by plane.”

They bought a few souvenirs, lit candles for the late grandfather Slava and for the health of his descendants, then headed downtown. When the mine closed in the late 1970s, the town was soon filled with bohemians and artists, and later with members of the LGBT community—then frowned upon in much of America. Stana wanted to see the galleries lined up one after another.

The first was “55 Main Gallery.” The walls were covered with paintings, jewelry, and bent metal shapes Slava couldn’t describe even under a polygraph.

“Look at this, Stana… someone bent a spoon and glued it to a wooden board. And that’s art?”

“That’s conceptualism, Slava.”

“I conceptually wanted to clean out the garage, but never got around to it. Imagine how many ‘artworks’ could be found there!”

Next stop: the Artemizia gallery. Walls full of graffiti, Warhol, Kusama, and in the corner the famous “Banksy rat.”

“You know who’d like this? That bald Šumadijanac who used to be a journalist, now a banker. He claims to understand these modern tricks. When I see this critter on the wall, my first thought is to call pest control.”

Among the exhibits was a sculpture of seashells, a bicycle, and a tennis racket.

“Is this art or did someone forget their stuff?” Slava asked a young artist with purple hair.

“It’s the journey of the soul.”

“Hmm, no wonder it looked familiar.”

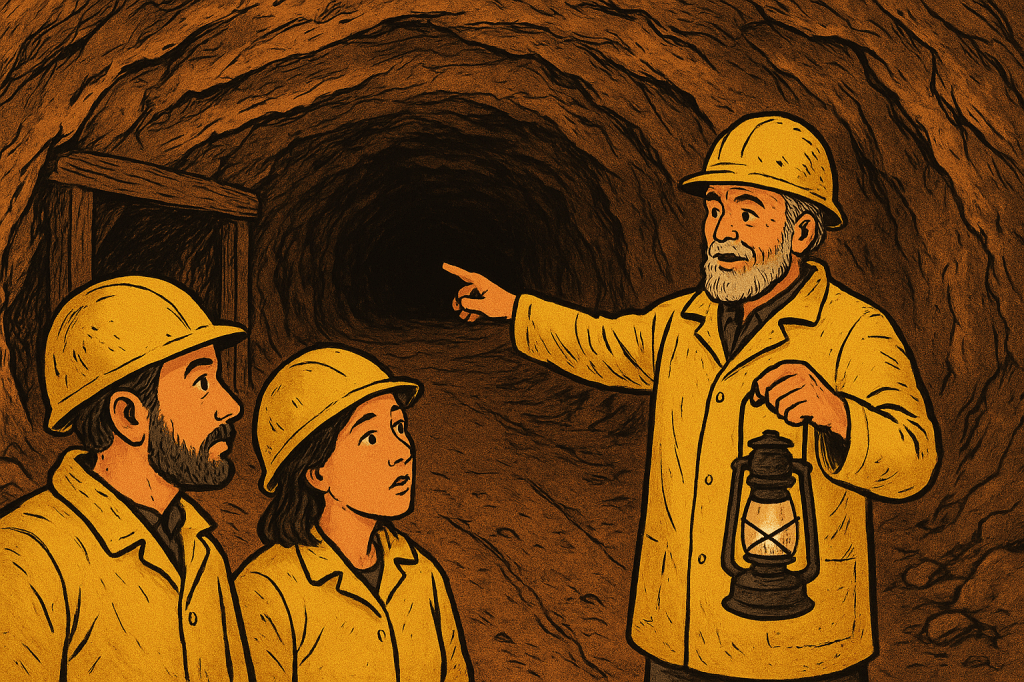

After fulfilling his wife’s artistic wish, the barber finally got his turn: the Lavender Pit mine. After viewing the open pit, they put on yellow raincoats and helmets and descended into the tunnel by a small mining train. The guide, an old man with Popeye’s arms, spoke calmly, as if counting minutes to the end of his shift.

“People worked here twelve hours a day, deep underground. No air conditioning, no cell phones… just sweat, dust, and copper.”

Slava cut in: “So what did they do when they got bored?”

“Worked harder, so they wouldn’t get fired.”

“My great-grandfather dug here too. They say he played tambura and sang.”

The guide smiled and pointed to a niche in the wall:

“Maybe he stood right here, where the air was a little warmer. I know some used to sing, to make the shift go faster.”

The guide continued: “The mine ran for nearly a hundred years, until it closed in 1975 when copper prices fell. Today, when we tell tourists how life was, many think we exaggerate.”

Slava waved it off: “I believe you, my friend. I know what it’s like to be stuck twelve hours under the lamp—on pensioner days in my barbershop, I shave and cut until my arms fall off.”

At dusk, they stopped at a restaurant. Slava ordered “Desert Winds Beans” and got beans with coconut milk.

“Is this beans or perfume?”

*“Vegan fusion,” the waiter replied.

“Listen, pal, I’ve eaten beans with ribs, with sausage, even plain beans—but never with coconut!”

Stana picked at her arugula salad, blushing at her husband’s complaints:

“Stop grumbling. A man should try something new.”

“Every time I tried, I regretted it!”

After finishing this so-called dinner, they drove back through the desert. The night sky was dark, only the cacti outlined by the moonlight. Slava was silent for a few minutes, then couldn’t resist:

“You know, Stana… I’m not sure about walking on the Moon, but today I went underground, saw where my great-grandfather worked, toured an artists’ town… and survived beans with coconut. Isn’t that enough?”

Stana laughed:

“You deserve a medal! Whether from Trump or Vučić, we’ll see!”

“A medal? Nonsense…” he waved her off. “That’s just barber talk—with a little salt, to make it sound like I opened the mine myself.”

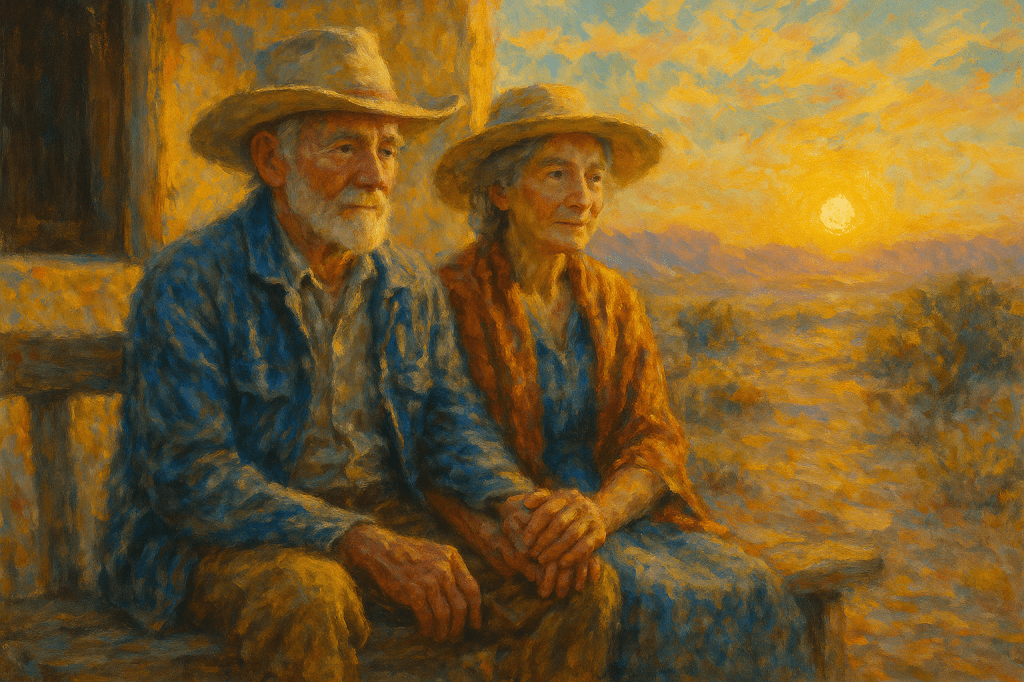

The car sped toward Phoenix, Leo Martin singing from the back seat. Slava pressed the gas and kissed his wife:

“See? Even without the sea, we had a lovely mini-vacation. Next year we’ll stay a whole week. Since when was Slava a cheapskate?”

Summer Stories from Arizona-Tucson: PUMPING IN A-117

At the far south of Arizona, Mount Lemmon and the Santa Catalina range formed a natural wall, reminiscent of an ancient time when people moved freely, loved openly, and lived together. All was peaceful until the day some gringo decided to draw a border with a ruler. North of the mountains lies Tucson, and to the south – times when no one asked for a passport. In the largest town in the American part of the Sonoran Desert, summer is not just a season, but a “torture chamber” for schoolchildren and students alike. The authorities, in their wisdom, decided the school year should begin in late July – when temperatures don’t drop below 110°F even in the shade. And people, as people do, long for shade.

It’s noon. The hot air clings to the skin, the streets are deserted, and the sidewalk shadows are as short as the patience of Tucson’s residents. In the middle of the desert, the Arizona State University campus rises like an oasis of knowledge, free thinking, and tolerance – but there are fewer and fewer who thirst for truth. Students move slowly, disinterestedly. On the walls: slogans – “Freedom for Palestinians in Gaza,” “Stop the Genocide,” “Silence = Approval!” Between lectures, on the yellowing lawn in front of the library, about twenty students protest. Despite their cries against atrocities, the atmosphere is subdued – lukewarm in contrast to the blistering desert heat.

Bane, a student from Serbia, arrived in the U.S. last month. Today was his first day of professional development. He sat on a low stone wall beside the path to the library, beneath a scraggly pine whose needles barely offered shade. In his hand, a plastic water bottle. He sipped from it now and then – not out of thirst, but to give his hands something to do. He watched the students walk by, slow and lifeless, like wind-up dolls. Posters, slogans on T-shirts… All of it evoked tragedies taking place far from this campus, far from Tucson, and even further from the American mind. The whole protest seemed limp – as if done out of obligation, not out of the desire to expose truth.

He tried to feel a sense of belonging, to believe in the values these young people claimed to uphold – at least on paper. He walked with his peers toward amphitheater A-117. A massive lecture hall at the end of the corridor – dark and perfectly air-conditioned. Professor Michael Greenberg stood before the board, mentally preparing for his first lecture to the freshman class. A short man in his late fifties, he wore a gray blazer. Wisps of thinning hair fell across his collar, dandruff clinging to the lapels. Fatigue weighed down his hunched shoulders. On the board, in rushed handwriting, was scrawled a quote by Aristotle:

“Where the law does not rule, there is no constitution. The law should be supreme, and even the rulers must be its servants. For if justice is equality, then all must be subject to the same rules.”

The students took their seats – some scrolling through phones, others scoping out their classmates. Bane sat next to a stunning Black woman and two guys he couldn’t quite place – either Arab or Latino. Back home, friends had predicted this: at first, he’d obsess over ethnicity, trying to decipher people’s bloodlines. But eventually, he’d stop counting red and white blood cells. In America, people from all over the world live side by side – racial math is a dead end. At least until Trump and his kind change the equation. And by the looks of it…

The professor sipped from a bottle, then closed it. As the noise faded, he began:

“Dear colleagues, future philosophers, let’s not waste time on introductions. Let’s dive right in. Who wants to comment on the quote on the board?”

A few students offered textbook platitudes – about law as the foundation of society, justice as a gradual conquest, nothing being absolute. The professor nodded along, encouraging further thought. Then a short-haired guy wearing a T-shirt with Cyrillic letters and a crossbody bag, raised his hand.

“Yes, go ahead.”

Bane hesitated for a moment, then responded with a question:

“Professor, were you at the protest out front today?”

Silence blanketed the room. As if on cue, every eye turned toward the accented student with a shirt that read – Pumpaj!

Greenberg slowly lowered his water bottle and leaned against the wall by the board.

“It’s expected of faculty to remain neutral. Our role is to teach, not take sides. If each of us shared our political opinions publicly, we’d stop being professors and start being propaganda.”

Bane’s neighbor by the door didn’t wait for permission – he shouted:

“The propaganda is already taken care of – by state-run and, frankly, most other media. If you intellectuals stay silent, what can we expect from some uneducated American getting all their info from Facebook?”

Though he agreed, Bane disliked being interrupted. He picked up where he left off:

“Aristotle says: A citizen is one who takes part in deliberation and in governance. If you remain silent, Professor, you’re not a citizen – you’re just a spectator. Academic neutrality becomes complicity the moment power turns into autocracy and you do nothing.”

A voice from across the amphitheater rang out:

“Exactly! Silence isn’t a defense – not when it comes to genocide in Gaza or fascism in America.”

Greenberg hesitated. Good pay, great benefits, funding for research… But hard to trample everything he’d learned about humanism, civilization, ethics…

“That’s a strong, though somewhat simplistic, interpretation of Aristotle.”

From the back row, a girl with messy curls and Israeli flags painted on her sleeves stood up:

“What about October 7th, 2023? What they did to us -was that justice? Should we just stay quiet and wait for terrorists to strike again?”

“Evil doesn’t stop by multiplying it,” Bane shot back. “An eye for an eye blinds both the victim and the aggressor – even when their roles reverse.”

A group of silent students in the far-right corner shifted. One heavyset guy wore a hoodie with an American flag. On the back: a semi-automatic rifle and the words: AR-15 for Trump.

“Easy for you to preach, foreigner. You weren’t here when our people died on 9/11. If you don’t like it, go back where you came from.”

“Yeah,” said his pale, ratty sidekick. “Trump’s guard is happy to escort you out.”

The professor wondered whether the debate had gone too far. He let it roll a bit longer.

Then a tall guy with a Pancho Villa mustache stood up. His shirt read: On stolen land, everyone’s an illegal. He looked directly at Greenberg:

“If you’re neutral about genocide in Gaza, how come you’re not upset when your President locks migrants in cages?”

The professor stayed quiet. But a new punch came from the far right – literally. A red-faced blondie in a MAGA hat jumped up:

“All you foreigners are the same. You come here, use our benefits, take our jobs, and then preach to us. We don’t care what Mexicans, Arabs, or people with weird alphabets think. Where’s this punk from anyway?”

“That alphabet’s called Cyrillic, you MAGA philosopher,” Bane snapped.

The professor tried to keep control:

“Everyone is free to speak here.”

“Yeah, and we’re free to say we’ve had enough of America-haters!”

Bane ignored him and locked eyes with Greenberg.

“Plato says: In democracy, people live as they please. Freedom is exalted above all, but when it becomes excessive, discipline erodes, laws are ignored, and democracy slides into tyranny.”

“See! Even Plato says we need order,” the MAGA crowd snickered.

But Bane kept going, quoting the philosopher:

“Plato also says: Democracy gives power to those with neither wisdom nor responsibility. And so, the state ends up in the hands of people unfit to lead.”

Silence.

Professor Greenberg used the pause to outline the semester syllabus. But “ceasefire” didn’t last long. A soft voice spoke up – from a girl with no slogans, no flags, wearing jeans, a white shirt, and loose black hair.

“Excuse me, Professor, but it’s not fair to interrupt someone in the middle of a debate. The guy in the Cyrillic shirt hasn’t finished.”

Swallowing hard, Greenberg turned to Bane.

“Please, go on.”

The student from Serbia rose slowly, looked at the young faces around him, and spoke plainly:

“I’m not here to lecture you. Or to win you over. I came to see what it’s like to live in a free country with functioning democracy. But I found fear – on the faces of people who have everything, except the guts to speak up. You ask why I care? Because silence equals complicity. If you mind your own business, you’re no different from those who disagree – and you’re helping your oppressors. I know how it feels to keep your head down to survive. I know how tear gas burns. How police batons sting. And the kind of silence you don’t choose – it’s imposed. You say: ‘Go home.’ Where, exactly? Back to where the government swings a stick and the people pretend not to see? Even there, students speak up. Even there, I don’t stay silent. Freedom isn’t American, Palestinian, or Serbian. It has no passport, no flag – but it has a price. You chose silence. I chose resistance. It may feel easier now – but one day, guilt will catch up to you. At least, for those who still have a conscience.”

The professor used the break to wrap up the lecture. Others stayed quiet. Some stared at the floor, some at their phones. Most just wanted out.

Outside, the sun was still scorching, the heat working overtime. At the edge of campus, Bane stopped and looked up at the mountains.

“In the land of the ‘free,’ telling the truth is the hardest thing,” he thought.

Summer Tales from Arizona: Scottsdale TH E W A L L

Scottsdale is a city where the wealthiest residents of Arizona have found refuge. The owners of enormous houses are doctors, jewelers, engineers, and political functionaries. Although it borders Phoenix, the people of Scottsdale are proud of their ZIP code and look down with disdain at the “poor folks” from the neighboring city. Desert Peace is one of many gated communities. At the entrance, there’s a barrier and an armed guard, so any traveler without an invitation is not a welcome guest. “You shall not pass!” the head of the homeowners’ association would shout if he happened to spot a random passerby near the gate.

In the community’s meeting room, the HOA was in session. After a fruitful discussion, it was time to summarize and make decisions. The president, a chubby man in his early seventies, with suspenders partially covering a T-shirt reading Make America Great Again and a pistol hanging loosely on his ample right hip, took the floor to deliver the summary:

“By majority vote, the homeowners’ association rules that the owner of property number 1988 on Understanding Lane must compensate his neighbor at number 1948 for damages and finance the rebuilding of the shared wall that was destroyed during the recent storm. If this is not done within seven days, the HOA will cover the repair costs and move the property line two meters into the responsible party’s yard. Meeting adjourned!”

Even the wealthy are not immune to small human flaws, but on Understanding Lane, the situation was growing more serious by the day—starting with the house numbers. In villa 1988 lived the family of retired botanist Amir Gazavi; next door, the house of jeweler Aron Schwartz bore the number 1948, followed immediately by 1990, 1992… When the local mailman complained about this inconsistency, he was immediately threatened with reassignment and labeled an anti-Semite. According to the zoning plan, backyards were separated by two-meter-high walls so that residents—whether they wanted to or not—minded their own business. The residents obeyed the strict rules set by the wealthiest among them—everyone except Gazavi and Schwartz.

Amir moved in first, living out his retirement peacefully with his wife and their dog Yasser, until the day Englishman Charles Attlee sold the house next door to jeweler Aron. From that day on, the stone-block fence turned into a wall of trouble and lament. The new neighbor immediately raised an Israeli flag, positioned so it fluttered directly above the Gazavi family’s living room. The next morning, neighbors noticed Amir armed with a ladder, tinkering on his roof. By noon, a flag with Palestinian symbols was flying.

Having handed the jewelry shop over to his son, Mr. Schwartz, in his later years, took an interest in computers and artificial intelligence. He completed various online courses and became fairly skilled. Amir, on the other hand, loved flowers, grass, and trees, turning his yard into a lush oasis in the Arizona desert. He had even trained his dog to respect the garden, so Yasser never soiled it. When Aron first peeked over the wall, he burned with jealousy. He waited until Amir went on vacation, sat down at his computer, and hacked into the irrigation system. When Amir returned, his botanical pride resembled his homeland: shriveled plants, withered flowers, a dried-up lemon tree—only the palms had survived. Yasser looked at him sorrowfully, as if apologizing for failing to protect his master’s handiwork.

Amir wasted no time. He ordered a drone from Amazon and paid extra for same-day delivery. After a crash course on YouTube, he learned to “pilot” the marvelous device. On Saturday, when Aron and his family went to synagogue, Amir launched the drone and destroyed the neighbor’s menorah-shaped fountain.

The next day, loud commotion came from 1948. Workers were busy repairing the fountain, while technicians installed a massive video screen aimed at the Gazavi home. When night fell, fiery speeches from Bibi Netanyahu blared first, followed by footage any reasonable court would declare genocidal. Aron, however, was proud of his “countrymen’s work” in Gaza. The noise agitated Yasser, who leaped over the wall and tore the screen’s fabric in seconds. The picture was gone, but not the sound—Hava Nagila Ve-Nismeha still blared from the speakers. Aron had had enough. He pulled out a taser and incapacitated his neighbor’s dog. Hours later, Yasser appeared at his master’s front door draped in a black-and-white checkered keffiyeh.

For the first few months, the petty hostilities ranged on an imaginary scale from harmlessly silly to risky and dangerous, but remained a secret between the two families on opposite sides of the wall. Then the neighborhood madness escalated…

The jeweler reported the professor for animal abuse, bringing the Humane Society to his door. Amir retaliated by accusing Aron of tax evasion, prompting auditors to spend days combing through the jewelry store’s books. Schwartz then sent an anonymous letter to environmental groups claiming his neighbor used excessive water to irrigate his restored garden; Gazavi responded with a letter to city hall alleging the fountain next door was built without a permit. Both dragged various institutions into their private war, but avoided the HOA, fearing expulsion from Desert Peace. These hostilities raged from October 2023 with no end in sight—until recently.

Every July 4th, America celebrates Independence Day. For the Gazavi family, it was a tradition to gather in full. Their son and daughter-in-law from Minnesota would come—and most importantly—bring their five-year-old grandson, Rami. Grandpa Amir prepared thoroughly for the visit. He chose toys carefully and stocked up on ice cream, cakes, halva, and kadaif. Rami played outside, eagerly awaiting nightfall for the surprise his grandfather had prepared—fireworks!

On the other side of the wall, preparations began by noon. Aron tidied the yard, arranged tables and chairs, and lit the grill early “just to let that villain stew in the smoke.” Fat dripped and sizzled, sending unpleasant-smelling smoke toward the neighbor’s yard, while Aron sat at his computer, meticulously preparing his holiday program. Around four, his son and six-year-old grandson Avi arrived. Though it was 113°F in the shade, the Schwartz’s wore dark jackets and black kippot. Father and son baked under the sun while the boy played near his grandfather’s fountain.

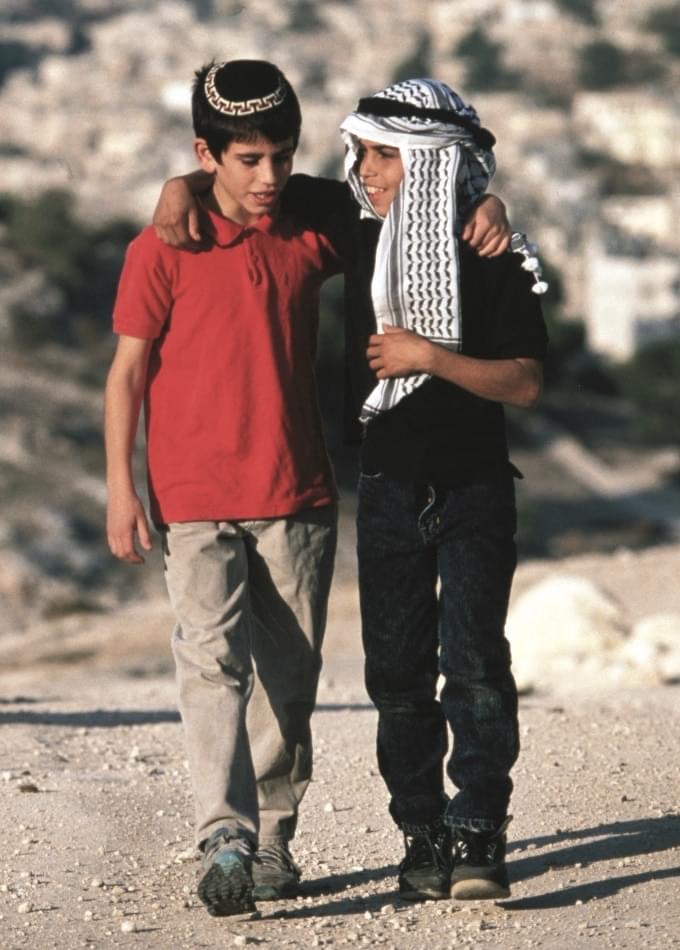

Mrs. Gazavi prepared a lavish spread: baba ghanoush and dolma to start, then roast lamb from “Yusuf’s Market,” tabbouleh salad, and fresh pita bread; baklava and tea to finish. Next door, the menu included matzah ball soup, kosher grilled beef, kugel, and challah bread; for dessert, babka cake and watermelon. The women set the tables, the men argued politics, and the kids—unplanned—began a peace mission. They met over the fence, quickly befriended each other, and agreed to meet out front.

They petted Yasser and played with Rami’s new toys (since Grandpa Aron rarely loosened his jeweler’s purse strings). They parted with a promise to watch the fireworks together after dinner. During the meal, the TV blared in the background—Al Jazeera at the Gazavis’, Channel Keshet 12 at the Schwartz’s’. At dusk, as the neighborhood erupted in celebratory firecrackers, grandfathers and grandsons stepped into their yards. Amir had set up his rockets and proudly asked his grandson’s permission to begin.

“Are you ready?”

“Like Paw Patrol before a mission!” the boy replied.

The barrage began: white, green, red… and again. With the first rocket, a little head peeked over the wall. Avi had taken his grandfather’s ladder to get a better view. As the neighbor’s fireworks ended, Aron launched his own show—a virtual display projected onto the Arizona night sky. Blue and white lines formed an expanded map of Israel, the Star of David, and finally the Israeli flag intertwined with the Stars and Stripes. Amir couldn’t believe his eyes. Looking down, he saw Rami on the ladder beside his new friend, both mesmerized.

The grandfathers soon erupted into another fierce argument, joined without hesitation by their sons. They all leaned over the wall like voyeurs in a public park. The boys ignored them at first, then whispered to each other and dashed off home. Minutes later, a racket erupted—Avi and Rami were banging pots with wooden spoons they had swiped from their grandmothers. Shocked by the boys’ protest, the old men fell silent, went indoors, and didn’t speak for the rest of the evening.

In the following days, the neighbors tried to mind their own business. One morning, as they were pulling out of their garages, the grandfathers even let a “good morning” slip. But, as Amir’s mother-in-law wisely said, “It’s not who you say it to—it’s who it’s meant for.”

At the end of the month, monsoon season began—rain, wind, then a big storm. The tempest swept through quickly and efficiently. Trees fell, cars were damaged, basements flooded, and on Understanding Lane, between 1988 and 1948, the wall collapsed. Unable to reach an agreement, they turned to the HOA.

And so, working backward, we return to the start of our story.

When the meeting ended and the decision took effect, Aron immediately filed an appeal, demanding that the Gazavi home be demolished because their dog had urinated on the wall, making it porous.

“Excellent idea!” the HOA president blurted. “We could put a gym there, with a nice restaurant.”

July 26, 2025

Tales from Arizona: Tombstone

THE LAST GUNSHOT OF WYATT EARP

In the lovely town of Tombstone, where the Santa Cruz River no longer flows due to drought, only one memory remains — a daily show in the center of town, nearly every evening. In the theatrical reenactment of the historic gunfight at the OK Corral, for two decades the role of Wyatt Earp was played by James Russell. But then age caught up with him — his voice and strength began to fail, and younger actors took over the show. It was five or six years ago when the director asked him for a drink after the “shootout.” James knew something was up. The tattooed brat of a director “carried a snake in his pocket” and had never bought a round in a saloon. That night, he told James that from now on, he’d be playing the villain — the outlaw Clanton.

From that day on, James was no longer the same man… Once a charmer and joker, beloved by both locals and tourists, now he sat silently in the corner of the dressing room — hollow-faced, eyes lost in thought.

In Tombstone, the sun scorches from early morning, and by midday, the asphalt begins to melt. Wooden houses crackle in the heat, and shadows retreat under porches. The town looks like a film set. The main street, with its saloons and faded Colt revolver ads, becomes a stage every day. At the far end, near the mock sheriff’s office and replica jail, stands an improvised set. Every day at high noon, the shootout at the OK Corral is reenacted. Visitors sit on wooden bleachers, waiting for gunfire and the triumph of good over evil.

Before stepping on stage, James would always twist a silver ring on the pinky of his left hand — an old habit, a charm against bad luck. The ring had been a gift from Mary, the woman he once loved madly but lost to his own stubborn pride. They had acted together across Arizona, performing side by side. Mary was fiery, witty, clever. Her hopeful, electric gaze always nudged him to wake from provincial slumber and leap toward adventure and uncertainty. She begged him to leave with her, but the “head sheriff” stayed put.

She left Tombstone and, after years of wandering, reached Hollywood. She never became a star, but made a modest career — appearing in background roles remembered only by those who paid close attention. They never saw each other again.

After one show, James sat outside the saloon, staring into the dry riverbed of the Santa Cruz. Just a trace remained where water once flowed — a few puddles, some greenish silt in the desert sand.

“This river is like my life,” he muttered. “The bed’s still here, but the water’s long gone.”

Suddenly, a man in a loud shirt approached. He looked like a tourist, but walked with the confidence of someone who knew exactly where he was headed.

“You played that fall and slow dying better than most professionals I’ve hired!” the stranger said.

James looked up.

“So, you’re a movie guy? If you buy me a whiskey, maybe I’ll fall over again.”

The man introduced himself: Roger, a producer of low-budget westerns. He was looking for someone to play an aging outlaw — a man of few words, whose eyes told the whole story. After three drinks, James began to open up. He spoke of acting, of love, and the chances he let slip. People told him he should go to Phoenix, maybe Los Angeles… But he stayed. Alcohol. This town. One makeshift stage — that was his life.

“How did you find me?” he asked, not really expecting an answer.

Roger took a sip of coffee and studied him.

“My mother recommended you. Mary Bush,” he said with a soft smile.

Silence. James coughed and looked carefully at the young man. The familiar lines of his face, the fire, the passion for art… He saw everything he had once loved in the woman he never forgot. He said nothing — just gripped his ring and twisted it slowly. He didn’t want words to ruin the moment.

He ordered another drink and asked Roger to leave the script and his number.

“Just so you know — shooting starts in a month,” Roger said as he toasted the local cowboy, packed his things, and drove off in a Tesla.

James called the Tombstone director that night to ask for some time off. The pretentious kid responded,

“Big deal, I can get any drunk to fall during the shootout.”

James swallowed hard, hung up, and muttered,

“You’ll see, you arrogant little mule, who you’re calling a drunk.”

He walked to the dry river, stared at the dusty bed, and thought about his wasted life.

“That role, no matter how small, is better than this wordless tumble in the dirt.”

He smoked a few cigarettes, went home, and found a package sticking out of the broken mailbox. He ripped open the envelope and recognized the handwriting.

My dearest Sheriff,

My sweet Wyatt,

You’ve met Roger. I’m sure you saw how much you have in common. I told him all about you — what a good actor and man you are. Take the role and come soon!

Yours, M.

He opened the large yellow envelope containing the script for Dust and Silence. The room was stuffy, despite open windows. No breeze. Just dust — and silence.

He brewed coffee, lit a cigarette, and read the script in one sitting. Then read it again. He texted Roger his acceptance. The reply came swiftly — with the address of a motel in Yuma where he’d be staying during filming.

A week later, he pulled out an old suitcase, the same one he once took on tour across Arizona. Mary had traveled with him back then. It still smelled faintly like her. He twisted the ring again and packed only the essentials.

Before leaving, he glanced once more at the Santa Cruz. The river no longer flowed — but it was still a river.

Maybe he too was still that actor, as they once called him?

At the bus station, he avoided familiar eyes. He wasn’t just leaving Tombstone. He was heading for something bigger: maybe… a new beginning?

That same evening, at the motel, he met the film’s director — a young man who clearly distrusted the amateur actor from a cowboy town. But then Roger, the lead producer, arrived. He ordered dinner, and the conversation lasted late into the night.

First day of shooting.

James put on the costume and waited for his scene. He didn’t have many lines. He played a man who had already said everything there was to say.

“Camera?” — “Rolling!”

“Sound?” — “Rolling!”

“Action!”

They filmed the scene where his character sits silently as the son he never met dismounts and walks toward the stranger. They stared at each other. James let a single tear fall, then embraced the young man tightly.

“Cut! Sold! Perfect!” the director shouted.

That evening, they sat outside the motel. The cowboy from Tombstone drank bourbon. The producer, beer.

“I hoped you’d come, but I was afraid you’d turn down the part,” said Roger.

“I hesitated… but I couldn’t say no to you,” James replied.

Silence.

“When I was little,” Roger began, “my mom used to tell me about you. Always with a certain caution. She loved you more than she cared to admit. I could only imagine you back then. Now I don’t have to.”

James raised his glass.

“To the roles we never played.”

“To a new beginning. Cheers!”

At that moment, the director appeared. He stood before the veteran actor, bowed slightly, and offered his hand.

“Mr. Russell, what you did today… I didn’t think silence could be louder than a monologue.”

James looked up.

“Neither did I. Not until today.”

They were alone again. Roger brought out a bottle of whiskey from the motel room.

“I’m still not sure if you’re my father.”

“I’m not either, son… but maybe that doesn’t even matter anymore.”

“How can it not?”

James looked up at the cloudless night sky and said softly:

“What matters is that now… we’re in the same frame.”

Filming wrapped.

Cameras packed, costumes sent to dry cleaning. Most of the crew had left. Only a few techs remained, plus the producer, a supporting actor, and one unfinished film — waiting for editing and an audience.

James sat under the motel awning, waiting for the cameraman to drive him back to Tombstone. Now, as a “star,” he had a ride arranged.

Then, a dark blue car pulled into the parking lot. A woman stepped out — wearing a cowboy hat and sunglasses. She walked slowly, but tall and steady. She stopped in front of James, removed her glasses, and looked at him for a long time.

“So you really came,” she said.

“When you called, I realized I didn’t want to die a bitter old man.”

They sat beside each other, quietly, for a while.

“I saw the way he looks at you,” she said. “The same way you once looked at me — that night after our last performance together. But Roger’s not yours.”

James said nothing. He stared into her eyes — still green, fiery, restless… just like before.

“His father was a producer from Chicago. Never acknowledged him. Never even saw him. So I invented a father. I told Roger his dad was just, a little stubborn, but always true to himself.

I taught him to walk like you. To keep quiet like you.”

James nodded.

“So… he grew up believing in a legend?”

“No,” she corrected. “He believed in the truth.”

James looked off into the distance — at the sky, the shadow of a tree.

“Thank you,” he whispered.

“For what?”

“For making me a father — without me knowing. And for letting me feel it before I go.”

Mary placed a hand on his shoulder.

“You’re not going anywhere soon. You’re too stubborn to die quietly!